You are here

- Home

- David Wield Symposium

- Session 3: Innovation, Engineering and Development PhDs

Session 3: Innovation, Engineering and Development PhDs

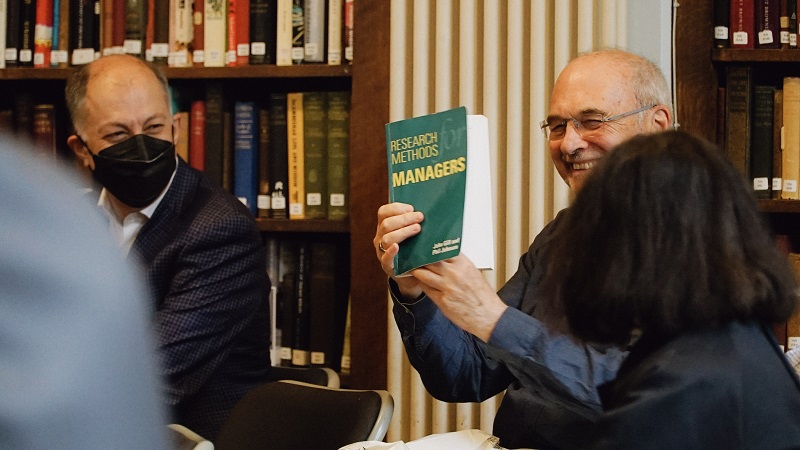

This session brings together four of Dave’s PhD supervisees to talk about their experience of being a doctoral student. Robin Roy chaired the session. The session focused on students’ experiences of doing a PhD at the OU in the broad area of engineering, innovation and development. Robin asked each student to say a bit about what it was like being supervised by Dave and co-supervisors and how the PhD affected their career. He asked a set of questions to answer in order of their graduation: Richard Heeks, Ivo Kovachev, Lizzie Babister and Kirsteen Merrilees.

The first question was: what did you do before the PhD and why did you decide to do it?

Richard: I guess my tale begins in 1976 in a school cupboard which contained a Teletype that was linked to the Reading University’s mainframe and being terribly excited that you could type things in and you’d get a reply from the computer. And so excited by that was I that I then did a year as a programmer for ICL back in the days of punch cards. A little later, a complete change of scene: sat in a local hospital in the centre of Nepal in Pokhara trying to record leprosy patient details onto a Tandy Microcomputer, not very successfully. These two experiences crystallise these two interests, one computers which I was very excited about, and the other what in those days we used to call the Third World and thinking where I’d like to be in future would be to somehow combine computers and the Third World. I had 2 years of the Third World and no computers after that and 3 years of research in computers and no Third World. Then there was an advert for a PhD studentship and it turned out that it was going to potentially be about computers and the Third World.

Ivo: I was a Computer Programmer. I’m from Eastern Europe and those were the first post-soviet years. There was no money at the time, and things had to change fast. So one of the things I did was to take the PhD under Dave and he was very patient with me and allowed me to do a field study. I went back to Eastern Europe: Bulgaria and the Czech Republic and even went into government and politics. But one day I was late with my latest chapter to him and I was wondering whether I should come back to Milton Keynes to meet him and talk about the chapter or deliver my invited speech to Parliament about privatisation and industrial policy. They didn’t understand privatisation in the early ‘90s and didn’t care at all about industrial policy so I decided to come for my chapter and Dave. That was the end of my political career. It totally amazes me even today that somehow we meet Dave, and he helps us, to develop, to think and he is very patient with us, exercising his soft powers, right? And then we go back to our very different career paths but everybody is pretty successful. I tried to do Silicon Valley in Eastern Europe and again it didn’t work at the time but now it’s working gradually.

Lizzie: My career started in the construction industry. I trained and practiced as an architect, moved over into working in humanitarian crises, worked with various different types of organisation, starting off with international NGOs (INGOs), some with very strong local partners. I was very lucky to work in several different continents seeing a variety of crises. Then I moved into government, worked for UK DFID for a while, back into INGOs this time in development and also on the organisational side of working in NGOs, particularly in financial strategy. At some point I saw things that didn’t make sense to me working in humanitarian crisis so doing a PhD seemed to be a way of getting the space to think that through. And that’s where I met Dave.

Kirsteen: I’m a Civil Engineer, I started out in consultancy design and then construction in the UK. For the past 20 years or more I have been working on infrastructure projects in international development. I started in Nepal in 1999 and have travelled to many countries and lived in many countries, and I’ve spent the past 12 years in Nepal again. Mostly I have been involved in rural infrastructure and construction and asset management, maintenance operations as well. I’ve also been an adviser to governments on policy and planning. In Nepal we have always been advocates of a labour-based construction approach employing local communities to build the road. That brings a bigger sense of ownership of the road. On my most recent project we were in an extremely remote and challenging part of the country. Nepal is all challenging and remote and difficult but this was really on the extreme, and there were very few people. The project was about social integration, but because we didn’t have enough people we had to advocate the use of equipment, heavy equipment excavators and there was a battle. There’s been this long debate in road construction about the use of labour or equipment and which is better. Is it better to use equipment and get a road built quickly so that people then get access to the benefits the road brings, or is it better to take your time and engage local people, get money into their pockets so that when the road comes they can access the benefits that the road brings? There were no answers in the literature and that is why I chose to do my PhD.

Robin asked for a bit more about the subject of the PhD and why it felt so exciting.

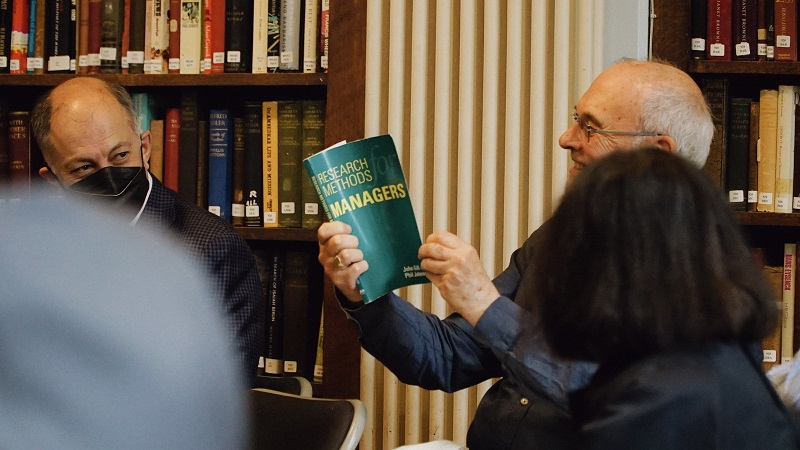

Richard: Discussions with Dave and [co-supervisor, the late] Ben Crow identified India as a place that things were happening with IT and development. Initially we fixed on what was then the largest computerisation programme in the world - the computerisation of the Indian Railways. I spent many happy days with a stopwatch in very old Dickensian style offices where clerks would pick various different tickets out of pigeonholes. Then going over to the new modern beautifully brightly lit offices with clerks in white coats with my stopwatch working out how much more efficient computerisation was. But also when I was over there I discovered that Indian programmers were going over to the States to undertake work for Western companies, a model called body shopping then. Nobody was writing about it at all and I thought “gosh this looks very interesting”, so I then plunged myself into that as well, so half my time in railway stations, Ministry of Railways’ library, and half my time as a very badly dressed, unkempt PhD student somehow being ushered into the offices of the CEOs of all of these major software companies, including Rishi Sunak’s father-in-law who then was not the head of a multi-billion dollar company. Infosys was operating out of a suburban house in Bangalore. I came back to the OU with reams and reams of data and Dave told me “actually Richard do you know what’s happened here? You’ve done two PhDs: one on the railways and one on Indian software and I think you’d better jump one way or the other”. I jumped for Indian software industry which of course was exciting and the right decision. We had no idea it was going to become this absolute massive phenomenon. And that’s been the blueprint for my research ever since, trying to find phenomena early on, start to research then write relatively formative papers. I’m so grateful to have had that model of how to do impactful research.

Ivo: It’s always difficult to find the best topic, best theme. I had the help of Dave and also I see here Tom Hewitt [co-supervisor]. It was not easy. But one approach was to be a bit contrarian, to try to be on the opposite side. And of course, I’m talking early ‘90s or mid ‘90s. Margaret Thatcher was seen as the best model, the same thing was invented in Eastern Europe. I don’t want to use the word Third Way, right, but common-sense policies that you implement at both national level, sector level and in companies can really help. That was my thesis. It was economic and development policy.

Lizzie: I was looking at overseas development aid, at state donors and how they fund their implementing partners in humanitarian crisis. As a case study I was looking specifically at shelter and settlements which is my field, that’s the link back to the construction industry. I was mainly looking at the journey that households go through when they lose their shelter and settlements and then the point at which the resources from state donors flow through implementing partners to provide assistance and try to unpick where it doesn’t align and why. In humanitarian crises implementing partners are told “right, you can apply for this funding and you can have it for 3 months”. You basically have to get as much done as possible within 3 months and it doesn’t matter if you’re trying to support people to recover their shelter and settlements or, say, get back their food security or improve their water and sanitation, it all has to be done in three months. I found through the literature review that a really small amount of literature on humanitarian crises looks at how a states decide which crisis to provide funding to. Or what effect it has on the ground. One exciting thing about my fieldwork was that people were really candid, they were quite appreciative of the space to be able to sort of offload some of their frustration and confusion about what was happening.

One exciting thing I discovered was around risk and the need for speed at the beginning of a rapid onset large disaster, say an earthquake. The need to get lots of money out the door quickly was conflated with spending it quickly - and that was quite strange. Donors wanted to say that “we have done a lot of things quickly, we have affected a lot of people, we’ve improved the situation in a massive way”. But the other thing was just basic financial exposure. If you’re going to suddenly release millions of dollars with very little due diligence, then you can’t release it for a long amount of time because that increases the exposure. And techies, like me, trying to get the job done, have very little awareness of these ‘higher level’ concerns. It was exciting finding out things that I wouldn’t have known if I’d stayed in any one of the roles that I’d had before.

Kirsteen: I think my starting point was that you’ve got this whole combination of factors to consider. There’s a very simple technical analysis that is easy, then you’ve got the financial comparisons, you’ve got social impacts and implications, you’ve got the politics, you’ve got the physical environment, there’s so many things that must all be taken into consideration in decision-making between something as simple as labour-based or equipment-based. I looked into social technical systems to set up a framework for this - I’m still doing my research by the way, I haven’t finished. I have developed a framework, a work domain framework for a road construction project that attempts to capture all of these different facets. Already in my head I know that I’ve got gaps in that work domain which is a little frustrating but of course that’s the whole point of the research. I have three case study roads. I’m a little bit too involved in my research, one of those roads is the one that I have just finished constructing, another one of my case study roads I was brought in at the last moment to finish off to get it finished on time, and then the other one is a government funded road. So those three roads all stem out from the same town, so they’re in the same location, the same kind of people, and a lot of the villages have all worked on our roads. The roads provide a very good set of alternative views on the institutional, the social side of these different approaches: one is pure labour-based, one is pure equipment-based and one is a hybrid approach.

Robin: Not ivory tower research at all - wonderful. So doing this PhD, what happened afterwards and how did the PhD affect your journey, your future path?

Richard: Another PhD student colleague saw a job at Manchester which turned out to be the one university job on the planet that was about IT and developing countries, so thank goodness I went up there and got it. At Manchester, we called it lecturing but actually it was very practical work in those days. We had public officials coming over from Africa and Asia who wanted to learn about computers. Research was encouraged and I carried on doing the work that I’d done under Dave and Ben and Tom and later published a book, the first book on India’s software industry [India’s software industry: state policy, liberalisation and industrial development, 1996, Sage] and carried on doing further research around software policy. So that obviously was a critical foundation to getting the job and then to carrying on the research that took me forward.

Ivo: I went into investment and doing the PhD under Dave and Tom helped me a lot and helps me nowadays all the time because part of the investment is this political thing, it’s a very big part. I do emerging markets, that includes with Britain nowadays right. Knowing how to analyse the politics is key. That is what I got from my PhD.

Lizzie: Right now my role is leading a research function for UN and Red Cross. I broker relationships between field-based humanitarian practitioners and academics, academic institutions, universities, think tanks, to try and ensure that there’s a decent evidence base for what’s happening in humanitarian crises. At the moment I’m launching two quite small studies, we’ve got a partnership that’s looking at connecting relief and recovery and looking at the transition to the longer-term. And there’s another study which is about the use of cash and cash grants in humanitarian crises and providing households with cash rather than in kind materials to repair, reconstruct. Some of that will touch on the research that I’ve done. Another project a little later down the line looks more widely at how shelter and settlements are funded in humanitarian crises - this almost directly overlaps with some of my PhD work so that’s exciting.

Robin: What about your experiences of being an OU PhD student, being supervised by Dave and other co-supervisors. Don’t hold back - the good, the bad and the ugly.

Richard: For me, the key thing was that we were treated like members of staff. Dave and DPP just treated us absolutely as equals, we were fully part of the research group meeting, so that’s actually the solid foundation that I was given. The one other thing I should just mention was that we were also summer school tutors and I don’t think anybody’s mentioned OU Summer School at the University of East Anglia which for me as a PhD student and I suspect for DPP generally was just such a fantastic experience: intense, deep, plus the discos. Sometimes people ask you ‘where would you like to go back to in history?’ and people say ‘when I met someone famous’ but I feel it would be to go back to OU Summer School.

Ivo: Well Richard said it very nicely, as in gentle, magic. Coming from my culture, for me Dave and Tom were like big brothers.

Kirsteen: It was slightly difficult to start with actually because I was abroad and the OU has this strange policy where PhD students are supposed to be Milton Keynes based. So Peter Robbins managed to pull some strings and get me a waiver so that I could stay living in Nepal and do my PhD. It was kind of bucking the system before you’ve even started. Peter was very, very helpful and between him and Dave they helped steer me. I’ve got all this practical experience but my understanding of the theory was completely missing, so they steered me in the right direction. Peter became ill but luckily he had given me that one big steer which put me on the right path. Dave and I have then continued for the past 2 years which have been extremely difficult for me with COVID because I had to evacuate my large project team in Nepal. I’ve just finished the data collection and now I’m back in the UK.

Lizzie: Dave’s going to hate this, I just feel amazingly lucky to have benefited from Dave’s amazing experience. I started off with three supervisors, managed to lose two of them, one sadly through illness, but Dave hung in there and Dave is just always there. I’ve never had to chase to find him, he was just always there, always enthusiastic. We’ve heard it quite a lot today - the words kind, generous, just like a rock. They say doing a PhD is like riding a bicycle only the bicycle’s on fire and everything’s on fire, and then you ride that bicycle into a pandemic. The person you want to be with in that situation is Dave. And I just want to take this opportunity to thank Hazel as well who stepped in at the end to be my second reader. How lucky am I to have had these amazing people as my supervisors.