By Maria Nita

Saturday, 11th November 2023, Armistice Day. Since the beginning of the war in Gaza in October 2023 weekly pro-Palestinian protest marches have been held in London, on a Saturday. On this occasion the march started at midday, an hour after the solemn annual ceremony at the Cenotaph – albeit this was eventually disrupted by a group of far-right counter-protestors attempting to reach the pro-Palestinian march and clashing with police.

Children’s Shoes Memorial – Extinction Rebellion protest action, November 2023, London (Photo Copyright: Extinction Rebellion Families)

In Trafalgar Square Extinction Rebellion activists showed their support for the pro-Palestinian march by staging an evocative children’s shoes memorial, for both Israeli and Palestinian young victims. Shoe memorials that mark collective tragedies draw inspiration from those commemorating the genocide against Jewish people, with well-known displays in the Holocaust memorial museums of Auschwitz and Washington DC. Based on some of the public accusations against the pro-Palestinian marches being antisemitic – they were called ‘hate marches’ by ex-Home Secretary Suella Braverman – even an inadvertent connection with the Jewish genocide may strike people as inappropriate, but it is important to emphasise what many protestors have stressed in public statements, namely that the marches are pro-Palestinian, not anti-Jewish.

Protestors are accusing the Israeli state of war crimes, and not the Jewish nation. Moreover, the ‘Jews for Ceasefire’ group have also been attending the pro-Palestinian marches, to oppose both the war crimes being committed by the Israeli state, as well as the criminal actions of Hamas – the terrorist group who, on the 7th of October 2023, attacked Jewish communities, killing civilians and taking hostages, including children.

The pro-Palestinian march, which started in Hyde Park and ended in front of the US embassy, called for the UK and US governments to ask Israel for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza. Many of the protestors’ placards pointed a finger to the seeming silent complicity of the UK and US governments for their failure to denounce and sanction the state of Israel, with such slogans as: ‘the UK and US shield Israel from accountability for its political crimes’, ‘their blood on your hands’, ‘bombing babies and killing children is not self-defence’, ‘genocide is not self-defence’, ‘stop war crimes in Gaza’, ‘it’s not complicated, it’s genocide’, ‘I can’t believe I have to protest against Genocide’, ‘one child is being killed every 10 minutes in Gaza’, ‘cease fire now allow aid in Gaza’, ‘stop the massacre’.

Protest action, November 2023, Edinburgh (Photo: David Robertson)

Globally, since the beginning of the Israel-Hamas war, there has been a rise in both antisemitic and Islamophobic motivated crimes, especially in the US, UK and Europe. At the peaceful 11 November 2023 pro-Palestinian march, with an attendance of some 300,000 people, the police reported that only a very small number of participants were being investigated for antisemitic statements – yet is important to distinguish between some of the statements of support to Palestine that are understood by some groups (but not others) as antisemitic, and the comparatively small amount of overt antisemitism at the events. The controversial chant ‘Palestine will be free from the river to the sea’ was interpreted by some as a call for the destruction of the state of Israel – in other words where would the state of Israel be, if Palestine were to take up the territory from the river Jordan to the Mediterranean Sea? Protesters defended the chant in media statements, explaining that it refers to freedom, self-determination and equal rights for Palestinians and Israelis, and an end to what has been described in some media and scholarship as the Israeli apartheid of Palestinians in Israel and the Palestinian territories (Pappé, ed. 2021; Rifkin, 2017). Protest banners citing late Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish sought to give voice to this collective experience of suffering of alienation, pointing beyond the current crisis: ‘“If the olive trees knew the hands that planted them, their oil would become tears”’.

Protest action, November 2023, Edinburgh (Photo: David Robertson)

Criticism and debate emerged from the fact that the pro-Palestinian march was going to be taking place on Armistice Day. The disagreement exposed the deeper ambiguity of Armistice Day: on one hand, recalling the atrocities of war and the need to build and maintain peace, whilst on the other hand, glorifying war through notions of martyrdom and the celebration of veterans – for an in-depth discussion of a century-long history around the complexities and controversies of the day, see Wolffe, 2019. Yet pro-Palestinian protestors on the Armistice Day march addressed the criticism of the march being disrespectful on their protest banners, by pointing to the appropriateness of asking for a ceasefire on such a day. Their slogans read: ‘Remembrance = action we take to prevent all wars’ and ‘Armistice for Palestine’. The controversy around holding the protest on Armistice Day brought up to the intersectionality of religious identity and issues of racial and ethnic equality and conflict, with protestors proclaiming on their banners: ‘“Never Forget” is not reserved for white people’ – thus addressing the far-right declared intention to keep the day as a national event.

The media and social media had abounded in claims about pro-Palestinian marches being infiltrated by Hamas sympathisers. Hamas, from ‘Ḥarakat al-Muqāwamah al-ʾIslāmiyyah’ (HMS) meaning ‘Islamic Resistance Movement’ – is a violent, fundamentalist movement founded 1987, with roots in the post-colonial era of the early 20th century, when European powers had colonised much of the Middle East. This means the movement has been active for close to 4 decades, drawing on a deeply rooted anti-colonial ideology. It is thus worth remembering that whilst the present humanitarian crisis in Gaza is unprecedented, the impact of the decades long Israeli – Palestinian conflict is not new, and its ongoing trauma has global reverberations and connections to ethnic and religious identities.

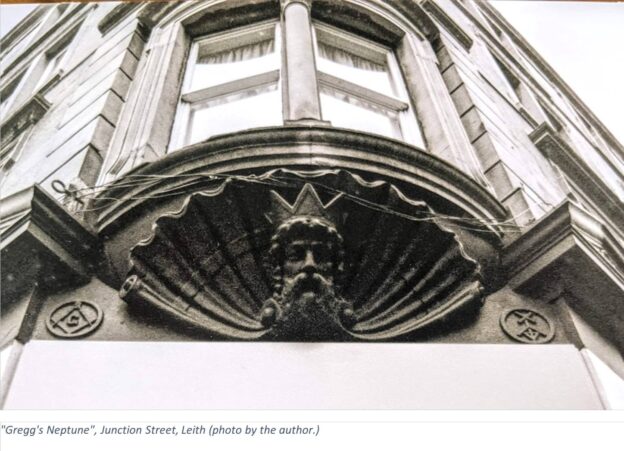

Figure 4 – Bacchus head, Maritime Lane, Leith (photo by the author).

Figure 4 – Bacchus head, Maritime Lane, Leith (photo by the author).