By Maria Nita (University of Wales, Trinity St David)

Death in the West vs. Romanian funeral practices

The modern funeral in the West is increasingly a celebration of life, marked by a depletion of ritual. The French historian Philippe Ariès (1974) claimed that in the West a reduction in the ritual associated with death and dying reflected an inability to accept death caused by the progressive growth in the importance of individuality. Thus ‘the death of the other’ – which was expected and accepted in the Middle Ages as a sort of reintegration in the ancestral community – becomes in modern times, according to Ariès, an unbearable occurrence which can no longer be mediated by ritual. In contrast, the Romanian funeral is still heavily dominated by folk customs, despite some studies suggesting a recent decrease in ritual due to various social factors, such as men taking up a more active role in organising funerals, an area largely considered the domain of older women, who act as expert maintainers of these traditions. (Popescu-Simion, 2014) Also in opposition to the Western emphasis on remembering the past by celebrating the life of the deceased, Romanian funerals are defined by a focused attention on the present, on the moment by moment developments of these rites and also, by an intense relational exchange with the dead body itself. I would like to explore here this engagement with the dead body as a sort of ‘death mindfulness’, leading to an identity transition of the deceased.

Mortu’ as a transitional state in Romanian funeral customs

In Romanian funeral customs, ‘the deceased’ is cautiously talked about as mortu’, a Latin-derived word also meaning ‘the dead body’. ‘Mort’ is, of course, the root word of many English words in this connotative field, such as mortuary, mortality or mortify. Family and friends, all dressed in black, sitting around a traditionally open casket coffin for a three day wake will adopt various attitudes towards mortu’ – from wailing at the head of the coffin, when overcome by grief, to quiet and even jolly conversations, whilst reminding each other to observe all the relevant customs. The customs range from smoky ‘ablutions’ of the body, circling the coffin with frankincense three times a day, to protecting oneself from mortu’ and its potentially dangerous, contaminative and unstipulated rapport with the living: ‘you mustn’t turn your back on mortu’ and if you do, find a small speckle on your clothes and put it on the coffin’, ‘we mustn’t let the candles burn out’, ‘you must put a black scarf on top of the main entrance’, and so on. This could be interpreted as a kind of funeral mindfulness – a practice that focusses one’s attention on the present moment. Towards the end of this process, as the body is taken out of the home or chapel and ‘sent on its last journey’, women rush to cover it with flowers and sometimes jewellery, or even makeup, giving it a puppet-like appearance. The transition is now complete and the frequent relational exchanges of the last few days come to an end.

Humour, death and hidden identities

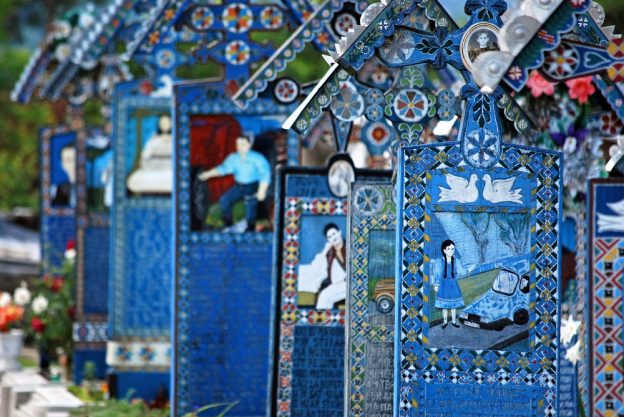

The ambivalent nature of these interactions seems to have, to some extent, a historical basis. Marina Cap-Bun (2012) shows that in Romanian culture we can identify two concomitant attitudes towards mortality: a pious reverence and abstract idealisation of ‘the departed’ – which Cap-Bun claims to be a later Roman influence, and an older indigenous attitude marked by an irreverent and humorous attitude towards death. This latter is embodied by the Merry Săpânța Cemetery in Romania, which, as the name suggests, abounds in funny and rude portrayals of the deceased. This attitude is also present in old funeral games in which mortu’ was the subject of concealment and trickery; in one extreme example the body was tied up with ropes and used as a puppet to startle unassuming visitors. Like with some shamanic practices dealing with disease, illness and death – laughter and mockery seem to become a gate for plural meanings through which a change or transition of identity is mediated. These polysemic funeral customs are also a constant reminder that one is engaging with mortu’, a transitory and ambivalent ‘being’, in a cocoon-like state. By focussing the attention on the dead body and the present time Romanian funeral rites and customs appear to provide a death mindfulness practice that seems largely forgotten or absent in the West.

Ariès, Philippe. Western Attitudes toward Death: From the Middle Ages to the Present. Trans. Patricia Ranum. The Johns Hopkins Symposia in Comparative History. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974.

Cap-Bun, Marina. 2012. “Attitudes towards Death in Romanian Culture and Civilization.” Philologica Jassyensia 8 (2):151-157.

Popescu-Simion, Florenta. 2014. “La Mort Dans La Ville Quand Les Hommes Remplacent Les Femmes.” Journal of Research in Gender Studies 4 (2): 1145-1150.