Stories and storytelling in time of pandemics

Set at the time of the Black Death, in 14th century Florence, Giovanni Boccaccio’s famous early medieval collection of novellas, the Decameron, tells the story of ten young men and women who take refuge in the country, as they try to escape the plague. They spend their time of isolation telling 100 stories, as if stories themselves could keep them safe, a bit like Scheherazade’s folk tales can extend her life in the One Thousand and One Nights. Like some special fabric of human culture, stories come in all possible contours, colours and patterns, and some are now worn out, torn, fraying or discarded.

Oracles and the divinatory arts can be understood as stories and storytelling practices that have an ambivalent status in our post-secular society. On one hand Tarot cards, Runes and Astrology are everywhere, just like our daily horoscope. On the other hand, these are often connected to fringe religious practices and thus fair game in the public sphere. For example, one recent tabloid article titled ‘Did psychics predict the [Covid-19] pandemic?’ (Delaney 2021) observed that ‘in these uncertain times, Tarot and Astrology readings are experiencing a renaissance’, yet when this columnist reached out for answers from online psychics and Tarot readers ‘they didn’t have a clue, just like the rest of us’.

Modern attitudes towards divination can be discussed from different perspectives, such as post-Enlightenment rationality, increased secularisation or even continuing public distrust towards some of the countercultural New Religious Movements responsible for the revival of Tarot cards and Rune stones, like the New Age Movement and Contemporary Paganism. Yet I would like to consider here divination as a form of storytelling, as well as oracles as stories, and explore what might they have to offer us at a time of increased uncertainty, when the environmental challenges of our world have been heightened and highlighted by the pandemic.

The past of divination and oracles

Divination was in many ancient cultures an important religious practice, used to ask about all matters – from the proper time and mode of religious conduct, to the coming harvest. Most scholarly definitions make reference to divine agency, as divination is ‘an attempt to elicit from some higher power or supernatural being the answers to questions beyond the range of ordinary human understanding’ (Loewe and Blacker 1981, 2). The Latin root divus means God like. However, oracles and divination had their early critics. As early as the 1st century BCE, the Roman stateman and orator Cicero was asking in his philosophical treatise, The Nature of the Gods and on Divination: ‘…how much weight we are to attribute to auspices, and to divine ceremonies, and to religion?’ as to not make ourselves guilty of ‘old women’s superstition’ (Cicero 1997 [circa 45 BCE], 145). In many cultural contexts during antiquity, religion and divination were intertwined, and supportive of each other, often in the face of philosophic and scientific adversity.

Oracles experienced a decline at the beginning of the first millennium, synchronous in very different cultures and noted by Plutarch, the Greek philosopher, in the 1st century AD. This decline of the oracles is akin to what, many centuries later, the German philosopher Max Weber (1864-1920) called ‘entzauberung’, ‘disenchantment’, when referring to a loss of enchantment with nature – yet in this case marked by a growing distrust in the divinity of oracles. In this disenchanted form, divination become less of a tool for predicting the future and more of a way of resolving controversies, according to some scholars (Thomas 1971). Hence, when there was a choice of two or more courses of action, the diviner was called upon to elucidate the better choice – perfectly arbitrarily. In his Religion and the Decline of Magic, Keith Thomas contends that in 17th century England, divination had become nothing more than a game of chance, used to shift ‘responsibility away from the actor, to provide him with a justification for taking a leap in the dark…’ (Thomas 1971, 288). This inexorable decline led according to Thomas to their complete demise, whereby ‘modern man’ does not confer any special meaning or value to divination other than the faith one places ‘in the playful flip of a coin’ (Thomas 1971, 298).

Modern divination, reflection and play

Online oracles in our 21st century clearly lack the reverence associated with ancient oracles. These days one can ask the caterpillar from Alice in Wonderland for advice, ask a Klingon for a Klingonese saying, receive a reading from the Psychic Fish and the Marzipan Fortune Piggy or consult Madame Ra’s Fortune Balls from Outer Space. The Sushi Fortune Teller asks the inquirer to choose five different sushi dishes and click on the brown sauce for an interpretation, or chopsticks to make another selection. These absurd and playful online oracles might appear to support Keith Thomas’ view. Yet it might be argued that divination in its postmodern expression, can adhere to what postmodernism stands for – deconstruction, playfulness, fragmentation – and yet maintain meaningfulness and significance.

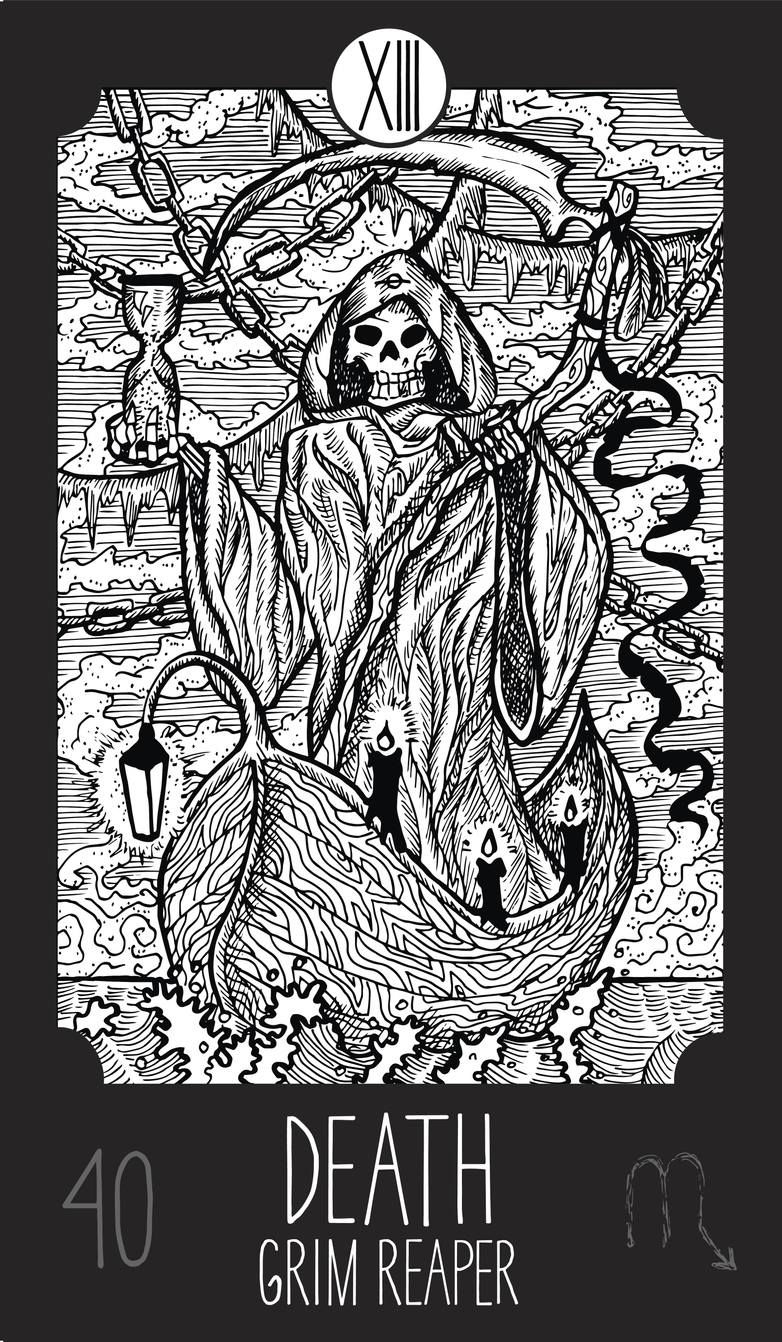

The revival of divinatory practices in the 20th century, alongside the revival of storytelling practices, brought important shifts to the old divinatory arts (Melton 1992). Contemporary Pagans in the UK began to unearth old legends and symbols: the rune symbols are after all stories from a Celtic past (Harvey 2007 [1997], 61). Although foretelling the future was still an obvious function, Astrology and Tarot card readings are now beginning to be advertised as tools for self-understanding and self-exploration – a key concern in the New Age movement. The Death card no longer means physical death for modern Tarot readers, but transformation or renewal. Seen as storytelling, divinatory practices, Tarot cards, Rune stones or Astrology, may be considered a source of reflection and learning. The inquirer can step inside the hero’s shoes and contemplate their own past, present and future on the backdrop of perfect stories of love and death. So how do they differ from other stories?

Piecing oracles back together

In the first half of the 20th century the Russian structuralist Vladimir Propp (1885-1970), in his famous Morphology of the Folktale (Propp 1998 [1958]), was attempting to understand folk stories or fairy-tale according to their form and structure. Propp observed that all fairy-tales followed a certain blueprint, a journey, and he identified a series of functions that could combine differently to form different stories. He enumerated thirty-one such functions, set in a loose chronological order, that could form the plot of any given fairy-tale, some of these being: absence, interdiction, violation, trickery, villainy, departure, guidance, struggle, victory, pursuit, rescue, difficult task, transfiguration or transformation, punishment and (happily) wedding…. Propp showed how the classic fairy-tale begins by introducing a status quo, the hero or heroine and their family, and then the story is set in motion by a necessary absence: the golden apple is stolen, the princess is locked away in a tower, the hero grows dissatisfied with what he has and wishes for something he is missing, and so on.

Propp’s functions resemble the units of the story told by any divinatory tool or oracle. The 78 Tarot cards is also a narrative, a complete story broken down into minimal symbols. The Tarot Major Arcana for example begins with the Fool, a card sometimes numbered 0, a symbol of inexperience and new beginnings, and ends with a card numbered 22, The World, a symbol of completion or the ending of a cycle. Inside this journey, card 13, Death, becomes a trial amid this cyclical journey. As broken stories or stories in pieces, divinatory tools allow for greater mobility, not to mention inviting us the inquirer inside this broken story, to make sense of it and put our own story back together.

Inside story: contemplating extinction

There is hope amongst eco-critics that the stories we tell each other now might help us address the ecological crisis (Haraway 2016). We do have our old stories of extinction, and according to environmentalist writers we need some new stories, ‘with better endings’, if we do not want old apocalyptic stories to become self-fulfilled prophecies (Plumwood 1997). So how come there are so many symbols of death and extinction in the Extinction Rebellion XR movement? The Death card is a story that reaches us through symbols and artistic media: the sulphuric green of the river Styx, the inescapable chains, the thick darkness of the underworld, the sickle and the hourglass. A symbol for XR, the hourglass is used by climate activists to remind us that time to act is running out, as they are asking us to reflect on species extinction.

It is perhaps not so much new stories that we need, but a different kind of engagement with all stories. In my research with Green Christians for example I found that in some of their storytelling practices the listener was asked to actively join in, an ‘inside story’ model I proposed as a useful ecological pedagogy (Nita, 2020). Actively inhabiting a story world holds the promise of helping us remember that we have a crisis on our hands, an important reminder, since there are plenty of stories that help us escape and forget. In his Storytelling and Ecology, ecological writer and storyteller Anthony Nanson tells us that when a story is good and well told, ‘the audience has space to discover their own response, in meaning and feeling and any consequent action’ (Nanson, 2021: 2), and that such a space for reflection can enable ecological agency and action. Nanson says that ecological stories can enchant the world, enable dialogue and facilitate change that can go beyond our cultural and linguistic limitations. Apart from a good story and a good storyteller, we might also need a good listener, what divinatory arts know as ‘the inquirer’, an active participant who can reflect on and make sense of the story and their own actions.

References:

Cicero, Marcus Tullius (106 – 43 BCE). 1997 [circa 45 BCE]. The Nature of the Gods and on Divination, translated by C. D. Yonge. New York: Prometheus Books.

Delaney, Brigid. 2021. ‘Did psychics predict the pandemic?’ Brigit Delaney’s Diary, Thursday 7th January 2021, The Guardian [online] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/jan/08/did-psychics-predict-the-pandemic-im-at-a-virtual-convention-to-find-out-who-knew-what-when [accessed 4th February 2021].

Haraway, Donna J. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

Harvey, Graham. 2007 [1997]. Listening People Speaking Earth: Contemporary Paganism. London: Hurst and Company.

Loewe, Michael and Carmen Blacker, eds. 1981. Oracles and Divination. Boulder: Shambhala Publications.

Melton, Gordon. 1992. ‘New Thought and the New Age’, in Perspectives on the New Age, edited by James R Lewis and Gordon Melton. Albany: State University of New York Press, 15 – 29.

Nanson, Anthony. 2021. Storytelling and Ecology: Empathy, Enchantment and Emergence in the Use of Oral Narratives. London: Bloomsbury.

Nita, Maria. 2020. “‘Inside Story’ Participatory Storytelling and Imagination in Eco-pedagogical Contexts”, in Storytelling for Sustainability in Higher Education: An Educator’s Handbook, edited by Petra Molthan-Hill, P., Heather Luna, Tony Wall, T., Helen Puntha and Denise Baden. Oxon & New York: Routledge, 154-167.

Plumwood, Val. 1997. Feminism and the Mastery of Nature. London: Routledge.

Propp, Vladimir. 1998 [1958]. Morphology of the Folktale. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Thomas, Keith. 1971. Religion and the Decline of Magic. London: Penguin Books.