By Richard D.G. Irvine

The listlessness that comes from staring at the same set of walls, as the days seep into one another. Difficulty summoning any interest or energy to do anything – in fact, the sense that there’s very little point getting out of bed in the first place. Inertia. From a monastic perspective such struggles echo in history.

Back in April, Fr David Foster, a Benedictine monk I met years ago during my PhD fieldwork at Downside Abbey, and now teaching at the Pontifical University of Sant’Anselmo in Rome, described the sharp shifts in emotion as Italy struggled with the wave of COVID-19 infection. The sudden decision to close places of learning feeling almost like an unexpected holiday; excitement quickly engulfed by the fear and uncertainty about the situation, anxiety of risk from the infection and grief amidst the rising deathtoll. And then lockdown. “Now, inevitably, it has begun to shift to a kind of stale boredom. Cassian of course had just the word for it – acedia. Yesterday I just went to the end of the drive, simply to look outside and enjoy (really enjoy) the sight of the wisteria in the road. That is the real pity – to miss the spring colours and smells.”

His words capture the feeling of constraint even within the monastery grounds; while monks might be thought of as experts in self-isolation, life for Benedictines is not typically one of total confinement to the enclosure. Yet in recognising and naming the struggle – this “stale boredom” which so many of us have been confronted with – what was striking was the way in which he reached back into the history of the monastic experience. John Cassian, born around 360AD, compiled and digested the teachings of those ‘desert monks’ who had withdrawn from society to live lives of prayer on the Nile Delta. In his Institutes he describes the dejection and weariness that was a frequent foe of the monks, and was denoted by the Greek word ‘acedia’ – the word itself might be translated as ‘lack of care’, though the struggle itself is a complex state that’s hard to pin down. He also explains that some monks associated it with the ‘midday demon’ described in the psalms they chanted (Psalm 91(90)) refers to “the scourge that lays waste at noon”).

The despondency of midday, when time feels motionless and directionless, is most vividly described by the monk Evagrius Ponticus, a key influence on Cassian: “First it makes the sun appear to slow down or stop, so the day seems to be fifty hours long. Then it forces the monk to keep looking out the window and rush from his cell to observe the sun in order to see how much longer it is to the ninth hour, and to look about in every direction in case any of the brothers are there. Then it assails him with hatred of his place, his way of life and the work of his hands.” This description resonates with the sluggishness of time in lockdown, the frustration and torpor of days with no end in sight.

Though I am currently on lockdown myself in Scotland, I have been taking the opportunity to connect online and on the phone with my friends from Downside Abbey, a community of Catholic Benedictine monks in South West England. Since the suspension of public church services as part of the effort to prevent the spread of COVID-19, the community have massively expanded their social media outreach as an effort to build connections with those who can no longer physically visit the monastery. (I have written about this outreach here.) A key part of this has been an attempt to offer support and spiritual resources to people who find themselves in the unprecedented situation of lockdown. As one monk explained, the audience that they had in mind was precisely “people asking themselves, what on earth am I going to do? … there’s a very real danger with that sense of confinement and isolation”.

A healing service broadcast live from the monastery on youtube and Instagram focussed directly on the ‘inner wounds’ of those struggling in lockdown. “We pray for those suffering from despondency and a sense of aimlessness, constrained as they are sometimes in very tight conditions”, dejected by circumstances that “seem, as it were, to be indefinite as well as unlimited”. Here again we are in the presence of the ‘midday demon’: a crushing sense of the monotony of directionless time and unvarying space, making it hard to keep purpose and meaning in sight.

Despondency, boredom, and structurelessness

A key motivation of the monks’ current outreach is the understanding that they have something particular to offer in this moment that a wider public could find valuable. Everyone has had to adapt to lockdown – but for monks, there is at least a sense that they have the benefit of having been trained for these kinds of circumstances.

From this perspective, to locate acedia in monastic history is not simply to render it an obscure concern of monks long ago – indeed, a contemporary Benedictine Jean-Charles Nault in his study of acedia, The Noonday Devil, describes it as ‘the unnamed evil of our times’ – but to try and understand the ways it might be overcome. Indeed, in sharing the principles of their life and Rule, what the monks are offering are the forms of structure designed precisely to combat the challenges, such as acedia, that were faced by the desert monks living a life of solitary struggle. Cassian’s Institutes, which would in turn influence the Rule of St Benedict which shapes Benedictine community life, are part of this trajectory of structure.

One video shared on the monastery’s social media reflects on how the monastic experience helps with the challenge of social distancing. Recognising the loss of routine as a major challenge at this moment, a key element highlighted is the pattern of monastic life as one of structured time; a structure which emphasises “the right amount of sleep, food, prayer, work”. Regularity is important. “It might be tempting to stay in bed all morning if you have nothing particular to get up for, or so it seems. But actually in the long run you’ll probably find that you feel much worse.”

One of the reasons acedia is so hard to translate or define is the wide range of struggles placed under this name. Cassian recognises it as a twofold attack: on the one hand, it leaves us spiritually exhausted to the point of not caring. On the other hand, it leaves us restless and wanting to run away – anything but this!

A passage from Evagrius captures the entwined nature of these responses – disinterest and restlessness: “When he reads, the one afflicted with acedia yawns a lot and readily drifts off into a sleep; he rubs his eyes and stretches his arms; turning his eyes away from the book, he stares at the wall and again goes back to reading for awhile; leafing through the pages, he looks curiously for the end of texts, he counts the folios and calculates the number of gatherings.” Finding it hard to care about the book you are reading, it suddenly becomes easy to entertain any number of distractions.

Here boredom, and our response to it, is recognised as a site of struggle for the soul. Little surprise, then, that the monks find themselves fielding questions about boredom during the lockdown. During a livestreamed Q&A session at the start of April, the Downside monks were asked “How often do you get bored or restless and how do you tackle it?” First the monks explored the challenges of boredom during prayer; for example, when praying the psalms over and over again, averting staleness by recognising that they are the prayer of the church, prayer shared in time and space, and that we pray them with and on behalf of people all over the world who are sharing the mood of that particular psalm. But “if we are talking about being bored with a job, or aspects of life well, that is life! Religious life is real life and sometimes we have to get on with it”. The advice is that boredom is not something to be evaded.

As another monk explained, the challenge of this time is to face circumstances with “heroic patience”. This follows directly from Evagrius’ advice of active endurance as a response to acedia: that we should persevere rather than making eloquent excuses for giving in to the instability of restlessness. We need to face boredom head on. Here lies a problem for an age of distraction: do we know how to cope with boredom?

Unable to accept boredom, the danger is that we seek any other distraction – any means of escape. Consolations of food, drink, social media, porn, gambling apps, are all close at hand, anything to take our minds off these dry days. There is also the danger of resentment and bitterness, as boredom leaves us ample opportunity to chew over perceived slights and wrongs, “which the evil one freshens in our mind from time to time”. Here, making present the voices from monastic history, is the relevance of identifying the ‘midday demon’ as a factor of life today. Recognising the ease with which boredom turns to despondency and distraction renders it a battleground, where we need to fight against “giving the evil one the opportunity to dominate our lives” and placing us in a state of “bondage”.

Remedies for acedia

Left to our own devices, such a struggle is hard – and it is against the backdrop of the solitary struggle of the desert monks that Benedictines understand the history of their structure and organisation, as a way of managing the struggle. The development of the cenobitical way of life (monks eating and praying together) is a recognition of our nature as a social species and the need to support one another; the importance of a shared timetable is a discipline against the distractions of boredom. (Chapter 48 of St Benedict’s rule states that “Idleness is the enemy of the soul”.) The circumstances of this moment – the isolation and routinelessness of lockdown life – are what makes the trials of the desert monks so familiar. Yet from the perspective Benedictines seek to share in their outreach, this is precisely why we need to find ways of recentering community and routine precisely as they are slipping away: “now these are times when we can do great things for others: a smile, a telephone call, a message”. As another monk advised (noting the importance of shared meals in the Rule of St Benedict), if you have coffee with colleagues at a particular time, keep doing that, even if it’s over skype.

In the teaching of the desert monks, another important remedy for acedia is work. Evagrius Ponticus advised, “give thought to working with your hands, if possible both night and day. … In this way you can also overcome the demon of acedia”. Manual labour is also one of the key remedies Cassian prescribes for acedia – an insight carried into the Rule of St Benedict with its emphasis on a balance of “ora et labora” (prayer and work). Yet while putting the body to work can awaken us from despondency, without structure it can itself become a form of obsession or distraction, hence the emphasis of ‘Benedictine moderation’ stressed in the Downside community’s monastic outreach, an approach which attempts to curb some of the individualistic excesses of monks trying to go it on their own: “plan your day so that you have things to do and achieve”, remembering that in everything we need balance, so “try not to be obsessive but do a bit of everything that is important”.

Naming and identifying the ‘midday demon’ in our own moment of stale boredom offers a sort of companionship from history: we are reminded that others have faced this before. Yet the message – that boredom cannot be escaped, but merely endured – is a stark one. Distilling the wisdom of the desert monks as a form of self-help, there is a danger that their emphasis on perseverance and endurance could turn into a form of machismo. However, this would be to miss the point. Drawing advice from life and from history is highlights precisely that acedia is not a lone struggle, but one shared in common with many others. And as emphasised again and again – for example in the healing service as livestreamed from Downside – this is a time of affliction, for acknowledging and asking for help with wounds. Here again the advice of those early monks drew from their struggles resonates: Evagrius presents tears as one of the most direct remedies for acedia. “Sadness is burdensome and acedia is irresistible, but tears shed before God are stronger than both.” In place of carelessness, a recognition of pain; in place of isolation, a sharing in one another’s pain.

Further reading:

Nault, Jean-Charles (2013) The Noonday Devil: Acedia, the Unnamed Evil of Our Times, translated by Michael J. Miller.

Bunge, Gabriel (2011) Despondency: The Spiritual Teaching of Evagrius Ponticus on Acedia, translated by Anthony P. Gythiel.

Richard Irvine is a lecturer in the Department of Social Anthropology, University of St Andrews, and Honorary Research Fellow in Department of Religious Studies at the Open University. You can contact him at rdgi@st-andrews.ac.uk

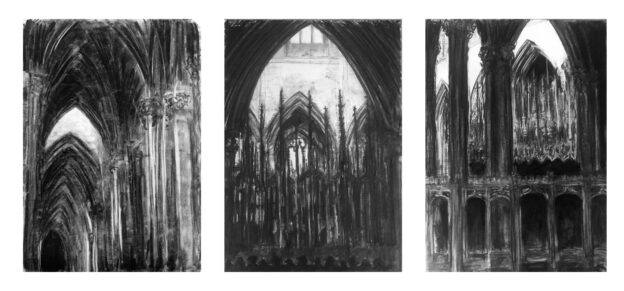

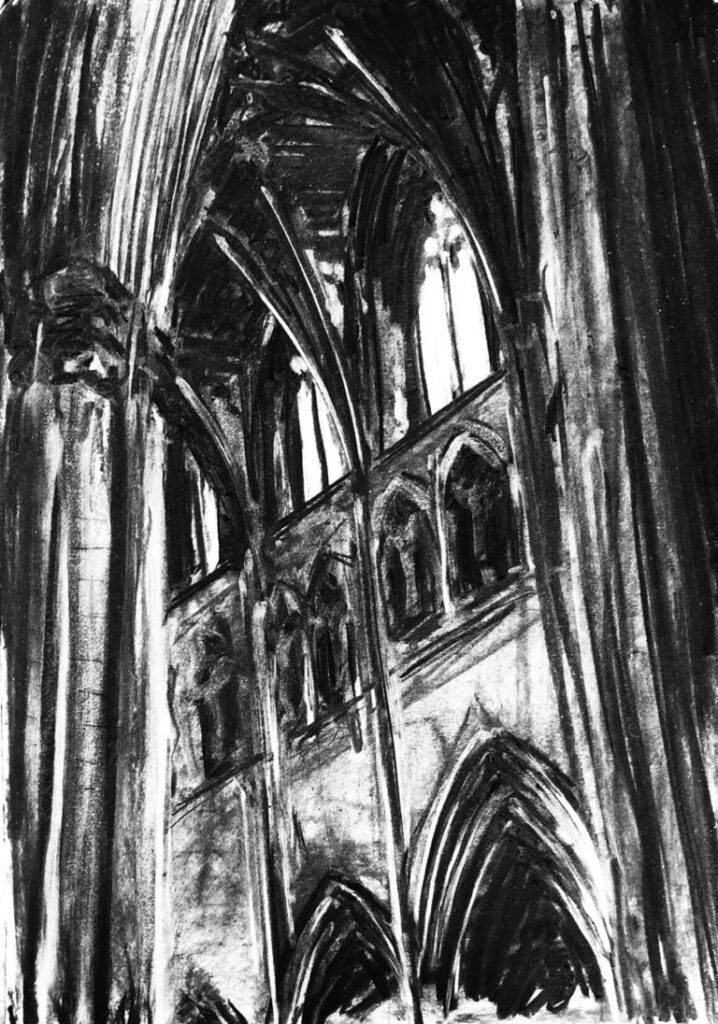

Illustration: “Downside Abbey triptych” (2019) by Oscar Mather, Lynch architects. oscarmather.com (with permission)