Professor Richard Holliman, The Open University.

“Evidencing impact is hard. Doing public engagement is hard.”

How many times have I heard versions over these phrases over recent years? “Too many”, came the weary reply.

It’s an obvious thing to say, but anything is likely to be a challenge to do well for the first time if you don’t plan ahead. Given that this seems so obvious, what’s surprised me is how often I’ve heard versions of these negative takes on the impact and public engagement agenda in recent months.

I’ve attended a range of events in association with preparations for REF 2021. I’ve heard these types of statements there.

I’ve been working with funders to explore how grants are planned for, assessed, monitored and reported. I’ve heard statements like these made by an unhealthy proportion of researchers during the course of this work.

And I’ve reviewed a good number of proposals over recent months that seek to generate and evidence impact. Guess what? Yes, you’re right. These arguments surface in discussions with some (not all) of these researchers.

Did I mention that it is eight years (yes, eight years!) since pathways to impact planning was introduced by RCUK? It is four years since REF 2014. It is three years since the completion of the RCUK-funded Public Engagement with Research Catalysts (Duncan and Manners, 2016).

So why are we still having the same arguments about the need to produce high-quality planning for the generation and evidencing of research impact?

The professionalisation agenda

I’ve written recently about the need for greater professionalisation in the ways researchers conduct engagement with relevant publics, stakeholders and end-users (Holliman, 2017).

There is clearly still a job to be done to ensure that organisational cultures and working practices match the principles of engaged research (Holliman et al. 2017), so that future leaders of engaged research can thrive (Holliman and Warren, 2017).

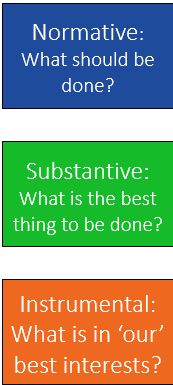

Exploring normative, substantive and instrumental rationales for decision making (see Holliman, 2017 for discussion).

The key issue is how these organisational changes and engaged ways of working are valued and prioritised. For a good number of researchers, working in engaged ways relate to questions of morality, validity and/or quality (Holliman, 2017).

Researchers working along these lines argue that we should engage, and we should do so in ways that are fair and equitable to those participating. If done well, it follows that engaged research can improve the quality of the research and the impacts derived from it (Holliman and Warren, 2017).

I was lucky to be encultured into my academic career by researchers who valued engagement (e.g. Jenny Kitzinger; Eileen Scanlon; Brian Trench). I’ve looked to pass on these ways of working through my academic career (e.g. Curtis et al. 2017).

Engaging the ‘hard-to-reach’ academic

The question shifts therefore to how we move beyond this group of engagement-committed academics. I’d argue that, from a researcher’s perspective, you can offer as many carrots as you like to encourage academics to change their practices. For these ways of working to be widely adopted requires changes to the way funds are allocated and reputations for excellence are gained.

Here are two obvious ways where the narrative around engaged ways of working will (#1) or could (#2) be changed:

1. The requirement to evidence impact in REF 2021 in an auditable form. We don’t know what this means yet in any great detail, but it’s clearly a game changer. If you can evidence high-quality impacts, funding will follow and your reputation will be enhanced.

2. Changing RCUK/UKRI assessment practices so that there’s a meaningful requirement to effectively plan for the generation and evidencing of impact within grant proposals. By meaningful I mean that Impact Summaries and Pathways plans should be scored. There should be a minimum threshold for a grant to be funded (no second chance) and the scores should count towards the overall assessment of the grant. Allocated funds will be made for high-quality research, allied with excellence in the planning for an evidencing of impact.

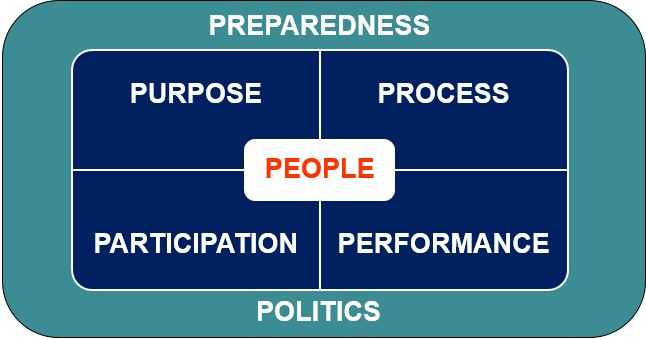

As a final point, I’d argue that, if you’re not planning effectively for engagement, you’re not demonstrating research leadership in the context of the impact agenda. What we need to encourage is rigorous, responsive and responsible forms of engaged planning to ensure that relevant publics, stakeholders and end-users can participate in ways that are meaningful to them.

Put simply, to give yourself the best chance of being successful as an engaged researcher, plan, assess, monitor and report. Here’s a page of resources to help: https://www.open.ac.uk/blogs/per/?page_id=7500

Planning for school-university engagement with research: preparedness, politics, people, purposes, processes and performance.

Acknowledgements

The research discussed in this paper was supported through the following awards: RCUK Public Engagement with Research Catalyst (EP/J020087/1); RCUK School University Partnership Initiative (EP/K027786/1); and a NERC Innovation Award (NE/L002493/1).