As I walked past Shakespeare’s deserted Birthplace on April 23 this year, I thought back to past celebrations of Shakespeare’s birthday…

Over the past twenty years or so I’ve walked in the invariably chilly Shakespeare birthday procession to lay flowers on Shakespeare’s grave and so on to a grand lunch in Shakespeare’s honour, rubbing shoulders with mayoral chains, national treasures, and occasional ambassadors. Before then, though, far from the Warwickshire epicentre of Bardolatry, deep in the American mid-West, I once gave a Shakespeare dinner to mark the date. Inspired by an American book washed up in the town’s second-hand bookshop, I concocted an enormously complicated menu which I inflicted on local Shakespearians. The preparations involved (squeamishly) taking out a contract on a local baby goat. I sourced edible musk, the only rosemary bush in Indiana, and a plastic mould for making a life-sized ice-swan. The menu ran to sack and claret, manchet-bread and sallets of scallions, boiled leeks, herbs and flowers, salmons pickled in red wine, roast kid stoffado with a pudding in his belly, and a dysshe full of snow, pausing for appropriate diversions and amusements before moving onto a formal ‘banquet’ featuring ipocras, shell-bread, dates stuffed with callishones, spiced peaches and the inevitable apples, and a gilded marchpane. There was a 4-page menu, garnished throughout with quotations from Shakespeare.

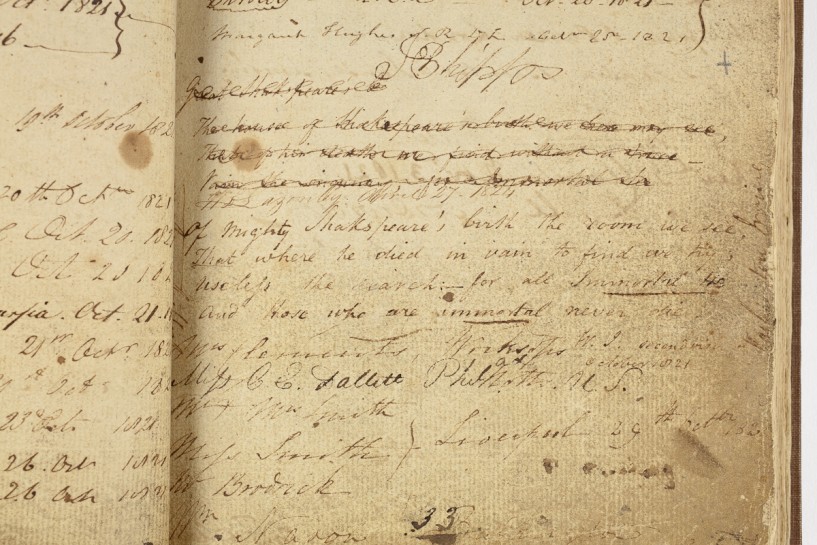

Two very different traditions of eating in honour of Shakespeare’s Birthday have emerged over the last two and a half centuries in Britain and America. In Britain the tradition of celebrating Shakespeare’s birthday with an annual dinner pre-dates David Garrick’s Shakespeare Jubilee of 1769 by at least fifteen years. By 1755 there was at least one group celebrating the date, according to verses ‘On the annual meeting of some Gentlemen to celebrate SHAKESPEAR’S BIRTHDAY,’ published in The London Magazine. Garrick’s Jubilee featured a great deal of dining on an unprecedented scale, including a Shakespearean breakfast and a banquet for upwards of 700. By 1827 the newly-formed Shakespeare Club in Stratford was providing not only a pageant and a procession, but a dinner for 200, followed by a public breakfast the day after. By 1830, the dinner was for 300, and the public breakfast was packed out, largely because, as usual, it was pouring with rain. The public breakfast at the White Swan on the next day (April 24th) was served to yet another 200, and the day concluded with a private dinner for the Royal Shakespearean Club and their guests for a mere 100, followed by toasts, presentations and songs. Apart from the sheer size of these dining events, what they had in common was the snob-value of the food, theatrically profuse in range, amount, and luxuriousness. This pattern persisted later in the century and in other clubs, as William Harris’s history of the Birmingham Shakespeare Club makes clear. Founded in about 1860 on the back of an older club which had regularly held dinners to celebrate the Birthday, they ran large-scale celebrations for the 1864 tercentenary, which included a ‘soiree’ for 250 on the 22nd (to which even ladies were invited) grandly provided with ‘special cards of invitation’, ‘an illustrated programme’, souvenir ‘ornamental badges’, a shrine mounted on a stage which held a bust of the Bard, a bust flanked with painted views of the church, the birthplace, Shakespeare surrounded by all his characters, and, mysteriously, ‘some oil-paintings’ and ‘Shakespeare photographs,’ all tastefully decorated with masses of symbolic evergreens. There were addresses, a performance of an original cantata, readings from the plays, and performances of Shakespeare songs, a public breakfast, and finally, an Anniversary dinner for 250 persons on the evening of the 23rd.

None of these menus required any historical research on the part of the cooks. No antiquarian desire to recreate a Shakespearean cuisine was involved. Instead, the sheer scale of the food on these occasions was meant simultaneously to demonstrate the wealth and importance of the guests and the importance and abundance of Shakespeare, the whole combined in a rite of national consumption. It would not be the English but the Americans who would translate this nationalist metaphorics of food into more self-conscious ceremonies of consumption. This impulse can be seen at its crudest and most exuberant in the all-male social event given on April 24th, 1891 by ‘The Britons of New York’ their ‘Annual Banquet of St George’s Society at Delmonico’s’. The pièce de resistance was two enormous sides of roast beef each weighing approximately 100 lbs (c. 50kg), followed by a large amount of plum pudding. At first glance, this dinner, flown with ex-pat nationalism, seems to have little to do with Shakespeare’s Birthday, except that one of the toasts given was to ‘The Memory and Genius of Shakespeare.’ But in fact ‘each topic on the toast list was adorned by a Shakespearean quotation’ and it is this practice of extensive quotation which distinguishes nineteenth-century American habits of eating in honour of the Bard. The Shakespeare Society of Philadelphia, founded in 1851 and still extant, provides an example of this habit. Membership of the club was men-only and by invitation. In addition to its regular reading meetings, at which members could expect light refreshments ‘soup, terrapin, salad and cheese, an ice, or meringue’ or ‘oysters, salad, and ale,’ followed by a demitasse and cigars, the club organised annual dinners, interrupted only by the Civil War years. These dinners, originally given in December, were moved on the tercentenary in 1864 to April, becoming Birthday celebrations, despite the difficulties – loudly lamented – of getting enough of interest to eat in that chilly and dismal month. Like the Birthday dinners being held in Britain, these annual dinners were the occasion for a display of profusion and luxury, for menus which translated into another medium the perceived richness and amplitude of Shakespeare’s works. What sets these dinners apart from their English predecessors is the practice of constructing ‘a bill of fare’, which took ‘infinite delight in weaving quotations from the plays into the evening’s scheduled proceedings.’ The menu of the Montreal Club in 1884 for dinner given for 21 uses quotation from the plays to comment upon the courses and conduct of this gargantuan feast. Shakespeare is made to remark slyly and jovially here to his fellow-diners on the pleasures of cessation between courses of this monstrous feast, on the possibility of indigestion after lobster, on the diuretic effects of asparagus, on the laxative effects of fruit, on the excellence and skill of the cooking, and finally to wish them a pious goodnight.

These masculine gatherings were very different to the gatherings of all-female Shakespeare clubs. If the men were enjoying extraordinarily protracted dinners in the private rooms of hotels or clubs, followed by toast after toast, the women were typically arranging to meet at each others’ homes in rotation. If the Shakespeare club of Aberdeen, North Dakota, is anything to go by, they were markedly more abstemious. In 1910, for example, after some years of serving ‘dainty refreshments’, the club agreed that every other meeting would offer a supper ‘to be served at 6.30, limited to six articles of eatables.’ Such modesty, however, masked fiercely competitive catering, eloquently attested to by the minutes. By the 1920s and 30s they were organising three formal dinners, one in October, one at Christmas, and one as a ‘guest day’ (which may have coincided with the Birthday), complete with an extensive musical and dramatic programme. The Aberdeen Club’s interest in ‘daintiness’ as opposed to deliberately antiquarian gargantuanness is probably not merely a reflection of changing times and the lack of professional kitchens. However different in its expression, this female Club was re-stating the notion of Shakespearean ‘refinements’ of intellect and the palate, here in a feminocentric fashion and setting. This was common to women’s clubs more generally. A little book published in Pasadena in the 1950s, entitled Dainties that are bred in a book: the Shakespeare Club cook book, dedicated ‘to those women whose vision, loyalty, and service, brought the Shakespeare club into being,’ deploys quotations from Shakespeare throughout that taken together imagine an orderly domestic universe, evoking the business of catering and cooking, delicious homely meals, a perpetual round of generous hospitality. If the men’s dinners take as their core comedic figure Falstaff and their core narrative a combination of Falstaff’s drinking at the Boar’s Head and Justice Shallow’s dinner for him in Gloucestershire, the women’s meetings take Perdita or Mistress Ford as their presiding genius – the Queen of the sheep-shearing feast, the merriest wife in Windsor.

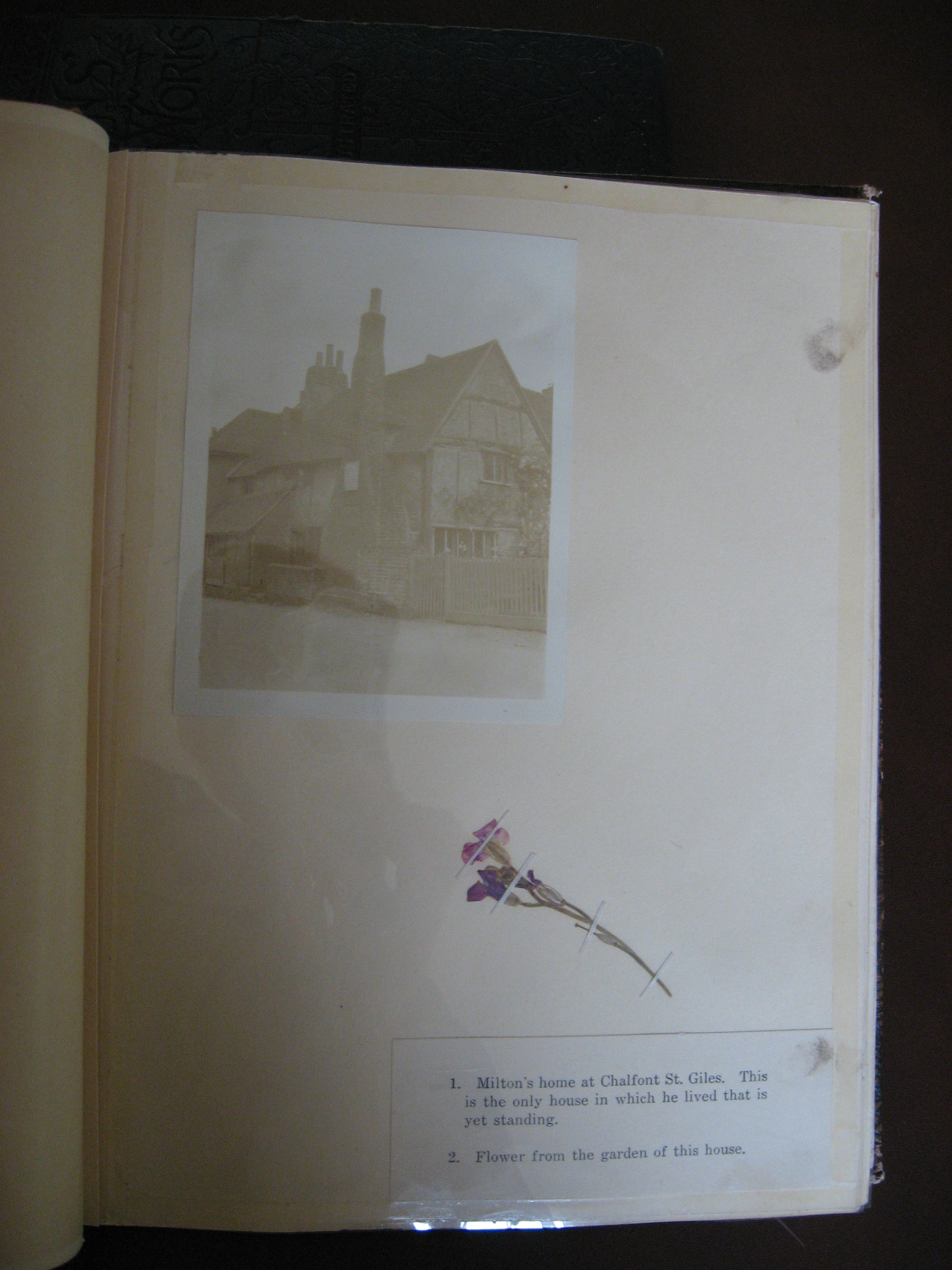

None of these exercises in Shakespearean eating, however, demonstrate much desire to eat actual Elizabethan English food. With the exception of gestures towards ‘the roast beef of old England’, the recipes and menus are contemporary in conception. It would take the best part of 100 years for Shakespeare enthusiasts to develop a taste for antiquarian cookery, and it would emerge as a delight of American ladies. Which brings me back to the book I found in that second-hand book shop. Entitled Dining with William Shakespeare and published in 1976, it took its inception from a social event run for the Eugene Oregon Shakespeare Club in 1966. The Oregon club had been founded as a women-only group in 1908, and was formally constituted as a club in 1912. In 1966, the author invited the club back to her home after a performance of Twelfth Night for ‘an after-theatre Shakespeare collation’ cooked up from recipes drawn from a reprint of Platt’s Delightes for Ladies. The antiquarian impulse did not exhaust itself with the menu, but extended itself to the table-setting. Predictably, a quotation-menu presented the dinner as a feast for the intellect and imagination. Madge Lorwin’s Renaissance parties caught on immediately. In quick succession over the next ten years she produced an Elizabethan feast with a ‘Shakespeare quotation menu’ for 400 in association with the University of Oregon Museum; another Elizabethan feast for 200 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Ben Jonson’s birth, this time with Elizabethan music and costumed waiters; and at least another two for the Ashland Renaissance Institute’s Shakespeare Festival.

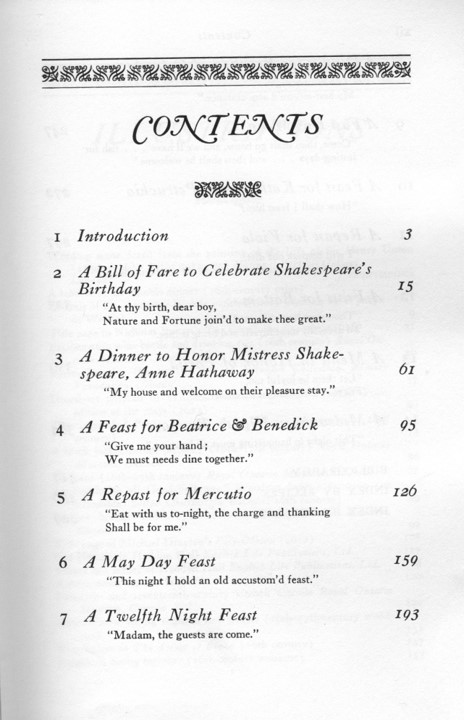

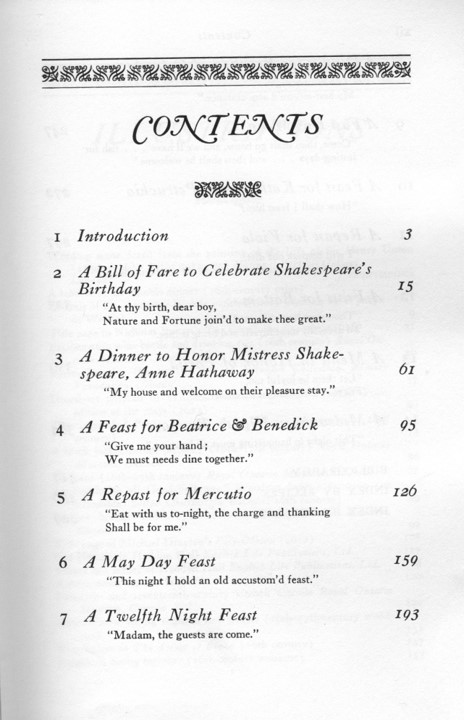

A much more scholarly production than the Pasadena cookbook, Lorwin’s book nevertheless shares with it a strong sense of the domestic, the biographical, the marital, the comedic, merrieness, and the seasonal: the menus include ‘A Bill of Fare to Celebrate Shakespeare’s Birthday’, ‘A Dinner to Honor Mistress Shakespeare, Anne Hathaway’, ‘A Feast for Beatrice and Benedick’, ‘A May Day Feast’, ‘A Dinner for Rosalind and Orlando’, and ‘A Midsummer Night’s Banquet’. This eminently practical cookbook provides a script for food-theatre, but it is also a piece of historical imagination, almost a form of historical fiction. It’s only those who are a long, long way from Stratford-upon-Avon who must travel to Merrie England by travelling back into their own country’s pre-history, and so it is only they who customarily use Shakespeare’s texts and Shakespeare’s food as the necessary vehicle.