Richard Danson Brown, Professor of English Literature

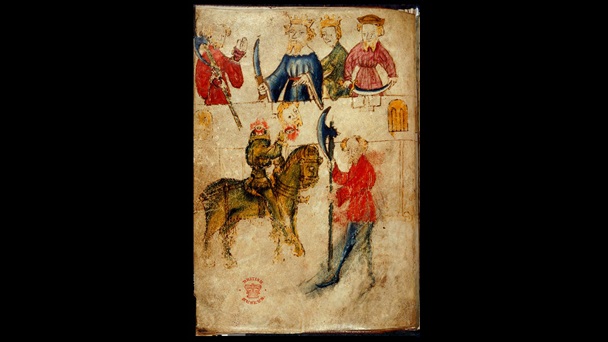

Four anonymous poems in Middle English: Pearl, Cleanness, Patience and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Created: c. 1400, North-West Midlands, Creator, Anonymous. Held by: British Library

One of the things that can be the hardest to explain to people who haven’t worked at the OU is how we teach. I’m not in this post going to get into the debates about teaching media (the pros and cons of digital and print have been energetically debated here and elsewhere recently) but rather want to focus on the pleasurable process of writing material for a new module, since I’ve just finished a first draft – in OU parlance, a D1 – on Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

This will be part of a new level 2 module, The Novel and Beyond, due for first presentation in 2019. (Level 2 is what the rest of the sector calls level 5, and again I’m going to resist the allure of a longer discussion of the manifold weirdnesses of OU nomenclature. If the OU were a religion, you’d see the success of its evangelical strategies in the readiness with which its staff adopt these slight but distinct deviations from normal registers: we work in codes which are just aslant of everyone else’s usages).

I mentioned the pleasurable process of drafting material. In the twenty years I’ve worked at the OU, I’ve always found this part of the job uniquely creative and enjoyable because that process is undertaken in a team environment which is typically energetic, questing and supportive. Added to this, the materials we devise will be studied by thousands of students: unlike conventional classroom teaching, OU modules are less ephemeral, being typically taught for around eight to ten years. That means your work – your enthusiasms and sometimes inevitably your errors of emphasis and judgement – will be shared by a large and shifting audience of students. At its best, working on a new module feels like you get the chance to say something perhaps you wouldn’t say elsewhere, about topics which you otherwise wouldn’t have a chance to engage with, to students and colleagues who are highly receptive to your efforts. That means that your register as a writer needs to be more sprightly – more demotic, less buttoned-up – than it would be in a monograph or book chapter.

This brings me to Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. As a specialist in Renaissance poetry, I often work with medieval texts and writers – Chaucer, Henryson, the Reynard the Fox stories are often on my desk; if pressed, Dante’s Inferno would probably be my Desert Island Book. But I’m not a medievalist, and I hadn’t anticipated getting a Middle English poem onto our curriculum. There are a range of reasons for this. In the dark backward abysm of OU time, a decision was taken that the Literature Department (as it was then) would focus chiefly on texts from the modern and early modern periods, with a smattering of works studied in translation; to all intents and purposes, Literature began with Shakespeare. Much of this was pragmatic: teaching Middle English at a distance was felt to be a step too far, and the staff and practices of the Department developed accordingly.

But new modules promote new ways of thinking. When the team designing The Novel and Beyond started work, we were sure that although we wanted our primary focus to be on prose fiction, we didn’t want that to exclude other genres, other ways of telling stories. After a protracted and increasingly nervous dalliance with Paradise Lost, I thought of Sir Gawain, and in particular Simon Armitage’s scintillating translation – could this be worth a try? It readily fitted into the module’s themes, and everyone was enthusiastic – much more enthusiastic than they were about poor old Milton. In the past couple of months, I have been working on this poem, which students will read in Armitage’s translation, with a smattering of Middle English terms introduced as needed. To adapt a line of Bertilak’s, when Gawain first arrives at the castle, if students listen, they ‘will learn the merits of language’ (l.918).

One of the perennial challenges of this process is integrating written materials with audio and video. When I consider the language and culture of Gawain, I do this through an interview with Professor Helen Barr, who is a specialist on alliterative poetry, and who taught me when I was an undergraduate. This interview outlines both what we know about the poem’s linguistic and cultural contexts, and most importantly, explains the poem’s stylistic recipe – how its alliterative verse form works. During recent months, Gawain has retuned my ear to the charming, distinctive idiom of Middle English alliterative poetry. I chose Armitage’s translation both because he’s a superb poet, and because his version tries to replicate the original poem’s alliterative patterns, which he neatly calls ‘the warp and the weft of the poem’ (p.viii).

Here’s an example from the stanza which Helen reads in our interview. In this passage, the poet describes the hardships of Gawain’s midwinter journey:

Nere slayne with the slete he slepte in his yrnes

Mo nightes than inogh, in nakede rokkes.

Armitage’s version isn’t a literal translation, and he finds some wonderful equivalents here:

With nerves frozen numb he napped in his armour,

bivouacked in the blackness amongst bare rocks (ll.729-30).

In the interview, Helen pointed out that one of the difficulties of alliterative poetry is the premium it sets on synonyms. The Gawain poet has a multitude of terms for man: burn, gome, rynk, tulk, wye – and, funniest of all to the modern eye, freke, a term which has survived, but with connotations which make it unusable in translation. The Gawain poet thought in synonyms to make his verse form work line after line. What a passage like this shows is that the alliterative pattern can generate evocative new phrases in modern English – ‘with nerves frozen numb’ is a nice periphrasis for ‘Nere slayne with the slete’, while ‘bivouacked in the blackness’ presents a new metaphor for Gawain’s grim journey.

What I particularly enjoyed about this aspect of our conversation was the way that it chimed with aspects of my own research. In my forthcoming monograph, The Art of The Faerie Queene, I argue that it is the limitations of a difficult form – in Spenser’s case, the intricate interwoven pattern of the Spenserian stanza – which enfranchise poetic experiment and new ways of writing. The Gawain poet and Armitage illustrate the same phenomenon. For all these poets, difficult forms lead not to the perhaps overpraised virtues of poetic concision but rather to an increased fullness of expression.

That’s what I hear in Armitage’s rendition of Gawain’s camping trip – a deliberate laying on of it thick, which, while it isn’t conventionally rhetorical, has a zip and a zest which mirrors the north midlands dialect of the original poem. That led me to thinking that there should be more experiment with these old, alliterative forms, and to read a different poem by the Gawain poet, also miraculously preserved in the single Cotton Nero A.x manuscript, Cleanness. Here’s a brief snippet from that poem – a couple of lines I found resonant in this summer of bright sun and elusive shade – when God appears to Abraham to warn him of the destruction of Soddom and Gomorrah:

He was schunt to the schadow under shyre leaves.

Then was he ware on the way of wlonk wyes thrynne (ll.605-06)

And here’s my own attempt at a poetic paraphrase:

He had shifted to the shadows under the shining leaves,

then he noticed on the bridleway three brilliant beings.

I’m not sure whether I’ll continue with this experiment, but the feel of this poetry, with its emphasis on a more elastic, variable sense of stress than the iambic pentameter of Spenser or Shakespeare is exciting and liberating. In brief, working closely with Gawain has made me newly aware of the oddness of English meters and the chances which have lead to the dominance of some forms rather than others.

Gawain is of course a quest poem. Gawain takes up the Green Knight’s challenge of the ‘lethal’ beheading ‘game’ (l.489), and has to undergo a series of tests which in his own reckoning diminish his self-esteem as he fails to be quite as honest, or as chaste, or as truthful (one of the poem’s key terms) as he would like to think of himself. Writing on this brilliant poem hasn’t been an ordeal to me, but it has reminded me of some of the things I love about working for the OU, which are in themselves related to the idea of a quest: the challenge of writing teaching material on something I am unlikely otherwise to research; the chance to blend different teaching media in what I hope will be an illuminating whole. And, as always, the desire to explain why this particular work might be interesting and worthy of study – how such a fantastical, unrealistic yarn may have some purchase on the way we live our lives today. I don’t yet know how students will react to the poem or my material, nor what my colleagues will think. But I am looking forwards to these encounters in a more optimistic frame of mind than Gawain when he sets off towards the Green Chapel in the last section of the poem:

‘So I’ll trek to the chapel and take my chances,

have it out with that ogre, speak openly to him,

whether fairness of foulness follows, however fate

behaves.’ (ll.2132-35)

Works cited

Simon Armitage, trans. (2009) Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. London: Faber and Faber.

Ad Putter and Myra Stokes, eds (2014) The Works of the Gawain Poet: Pearl, Cleanness, Patience, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. London: Penguin ebook.