Last summer, we ran a blog post that included some suggestions from colleagues in Classical Studies for classically-themed ‘days out’ in the UK; this year, we thought we’d catch up with a few colleagues on their ‘classical’ adventures over the summer vacation. So, as the nights begin to draw in, we look back at some of our recent encounters with the classical world through archaeological sites, theatre, films, and more. We’d love to hear about your recent classical encounters too … why not tweet us over at @OU_Classics?

————

Eleanor Betts

I’ve meant to visit Tuscany for years, and finally made it this summer. If you haven’t visited, do! First, I was digging on the Albagino Sacred Lake Project. Beautiful location for an excavation, despite the mosquitoes!

The Albagino Sacred Lake Project

Aside from trowelling clay, my role was to make a phenomenological survey of the site. Why were people in the middle of the first millenium BCE leaving bronze figurines in the countryside? We recorded the sights, sounds, temperatures, birds and beasts in and around Albagino. Our working hypothesis is that people travelling between Prato and Marzabotto may have passed through Albagino, taking advantage of the fresh water and ample provisions there.

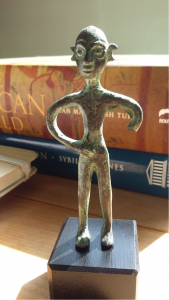

After the dig I made a whistle-stop tour of Tuscany. My first, and favourite, stopping place was Volterra … where I found this chap:

Replica of an Etruscan votive figurine

Votives aside, Volterra was one of the significant settlements of Etruria, and is well worth a visit. Enjoy the archaeological museum, Palazzo Priori and wandering the town’s medieval streets. From there I went to Vetulonia (3rd– 2nd century BCE), which has another lovely archaeological museum and the best basalt street I’ve seen outside Rome!

Most of what we know about the Etruscans is from their tombs. Each place has its own character, suggesting localised beliefs and practices. I visited Volterra, Vetulonia, Populonia, Chiusi, Tarquinia, Orvieto and Cerveteri, and can recommend them all. I found the house tombs at Crocofisso del Tufa (Orvieto) and Cerveteri the most resonant. Going inside any of these tombs feels like walking into someone’s house – and they’re homely! Oh, and Tarquinia has amazing painted tombs, such as the Tomb of Hunting and Fishing (Tomba della Caccia e della Pesca).

The Tomb of Hunting and Fishing

————

Elton Barker

I confess: I’m not much of a theatre-goer, even though I love (and research) Greek tragedy. I much prefer cinema, perhaps because it comes with less class baggage. But this trip to see a staging of Sophocles’s Electra at the end of August was going to be different, since the play was being performed outside in a semi-circular theatrical space (thus appealing to my classical sensibilities) in the forest that overlooks Greece’s second city, Thessaloniki.

In a word: Wow. This adaptation by the National Theatre of Greece (under the direction of Thanos Papakonstantinos) was something else! At one level, it appeared quite traditional: the play wasn’t located in a contemporary setting; the costumes were simple, bordering on the stylised; it used music throughout; the chorus sung *and* danced; the text wasn’t excised or adapted in any way (other than it being the modern Greek translation). But it was like nothing else I had seen. As you’ll see from the photographs, the stage was stark in its simplicity, an effect that was further amplified by the simple, almost abstract costuming of all the actors. Not only did this help focus attention on the gestures, movement and interactions of the actors; it also helped to defamiliarise the action and detach it from any particular setting, whether classical or modern. This is something, I think, that Greek tragedy generally manages to do: that is, to speak to audiences not bound by space or time. But one costume did possibly have a contemporary resonance: the clothing of the chorus seemed to me to be a pristine white version of the clothing worn by the handmaids in renowned TV adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale.

Electra reachers out to her sister Chrysothemis

Controlled and in control, this was a chorus of and for our time, gaining power through their collective action. A *spoiler alert* #metoo movement. Unlike every other chorus I’ve ever seen, this chorus sung and chanted in metre throughout in unison. They also moved as one, like polished mannequins, often with minimal gesture of forefinger touching the thumb, like a Greek orthodox Christ blessing his congregation. Then, as the play hurtles towards its terrifying climax (the matricide; the forever deferred murder of Aegisthus), they transform, as Electra’s hatred and bitterness finally comes to affect and infect them. They transform, indeed, into those terrifying presences who are notably (notoriously) absent from Sophocles’s play. As this performance made real what is only ever hinted at in the text, the chorus take up Electra’s murderous, blood-curdling calls for her brother to strike down her mother, for vengeance to strike down Aegisthus, by transforming into screaming, writhing Erinyes (the Furies). This wasn’t so much a tragedy as a full-on horror show. It was, quite simply, thrilling and has stayed with me, goading me to think and to respond, ever since.

Electra and the Chorus

————

Jan Haywood

Towards the end of the summer break I went to see an incredible new film by Zhao Ting entitled The Rider. The film tells the story of a hippophile named Brady, who recently suffered a major head injury after his horse fell on him while he was bronc riding at a rodeo event. As the film begins, we follow Brady’s troubled road to recovery, and remain on tenterhooks throughout, wondering whether or not he will choose to ride again. Although the film bears no obvious resemblances to any specific source text from the ancient world, I found myself continually transported to the literature of classical antiquity; for instance, in one of several stunning sequences, Brady is shown wrangling a particularly stubborn horse, aptly named Apollo. The scene captures powerfully the profound trust between horse and human protagonist, who communicate with each other silently through a series of dance-like movements.

Brady comforts Apollo in The Rider

This kind of special devotion to and care for one’s horse is deeply ingrained in ancient Greek culture; one only need think of Alexander the Great’s famous steed Bucephalus who purportedly served the Macedonian King in several battles, or indeed the Trojan hero Achilles and his immortal horses, Balius and Xanthus, who, in Book 17 of the Iliad, weep at the sight of mutilated Patroclus. Watching the film, I was also reminded of the fourth century BCE Athenian writer Xenophon and his equestrian treatises, namely the Peri Hippikes (‘On Horsemanship’) and Hipparchicus (‘The Cavalry Commander’). In the former of these two works especially, Xenophon includes precisely the kind of exacting details on how to achieve the ‘best of himself and his horse in riding’ that is so vividly depicted throughout the film’s delicate, long takes of Brady and his beloved Apollo. So, a film that is not about equines in antiquity, but nonetheless one that lends itself to contemplation on the values of horsemanship that were deeply ingrained in the classical world.

Alexander and Bucephalus, detail from a Roman floor mosaic, Pompeii

————

Jessica Hughes

This summer I continued my travels around the sacred sites of Campania, this time exploring the regions of Cilento and Vallo di Diano. It was a wonderful trip, and now – back in England as the autumn leaves turn gold and brown – my mind keeps returning to one place in particular: the Early Christian baptistery of San Giovanni in Fonte, which is located just a few hundred metres from the Charterhouse (‘Certosa’) of San Martino in Padula. I’m sharing some video footage that I took at the site, which is thought to have been built on top of an earlier Roman site, perhaps a nymphaeum. In this short sequence, you can see the spring water which the sixth-century writer Cassiodorus described as “a marvellous fountain, full and fresh, and of such transparent clearness that when you look through it you think you are looking through air alone” (Variae 8.33). The camera then moves into the interior of the building, towards the huge ‘font’ in which those receiving baptism may have been fully immersed. You’ll get a brief glimpse of some fragmentary frescoes of Saints, which have been dated to the tenth century, and which may originally have surrounded an image of Jesus. I love the way that the water casts its dappled reflections on the ceiling – and I can’t wait to visit this ‘marvellous fountain’ again in the winter.