LGBTQ+ History Month Open University, Source:

Each February, LGBTQ+ History Month invites us to celebrate LGBTQ+ culture, achievements, and activism. This year’s theme is Science and Innovation, encouraging us to reflect on how data, research, and critical enquiry help drive positive social change. Mathematics is central to that mission: it sharpens our reasoning, challenges assumptions, and equips us to analyse inequalities that shape people’s lives.

You can read about the origins of LGBTQ+ history month here: LGBT+ History Month 2026 | Stonewall UK.

LGBT+ History Month 2026 logo, Schools OUT UK.

Source: https://lgbtplushistorymonth.co.uk/lgbt-history-month-2026/

LGBTQ+ Mathematicians

For students and colleagues in mathematics, this month is also a chance to highlight LGBTQ+ mathematicians whose work and advocacy continue to transform STEM. Here, we spotlight four figures whose contributions illuminate not only mathematical innovation, but also the importance of visibility, justice, and community.

Alan Turing (1912–1954)

Alan Turing (1951). Photograph by Elliott & Fry. Public domain. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Alan Turing’s influence on modern science is hard to overstate. A founder of theoretical computer science and artificial intelligence, his wartime work on codebreaking significantly shaped the course of the Second World War. Yet despite these achievements, Turing was persecuted by the British state for his sexuality, a stark reminder that scientific brilliance flourishes best in conditions of dignity and inclusion. Today, Turing remains both an icon of mathematical innovation and a symbol of the ongoing work needed to ensure LGBTQ+ individuals can live and work openly and safely.

You can listen to some audio recordings about Alan Turing on Open Learn, here: Alan Turing: Life and legacy | OpenLearn – Open University

Autumn Kent

Autumn Kent. Source: https://500queerscientists.com/autumn-kent/

Autumn Kent is a topologist whose research explores geometry, topology, and moduli of Riemann surfaces. She has published extensively and received several major awards, including a Simons Fellowship. Kent is also a pansexual trans woman and a prominent advocate for LGBTQ+ inclusion in mathematics, organising the LG&TBQ+ conference to support collaboration between LGBTQ+ mathematicians working in geometry and topology. Her work exemplifies how mathematical creativity and community activism can reinforce each other.

The most recent LG&TBQ+ conference (LG&TBQ2) was held in 2025: LG&TBQ2: geometry, topology, and dynamics | Fields Institute for Research in Mathematical Sciences

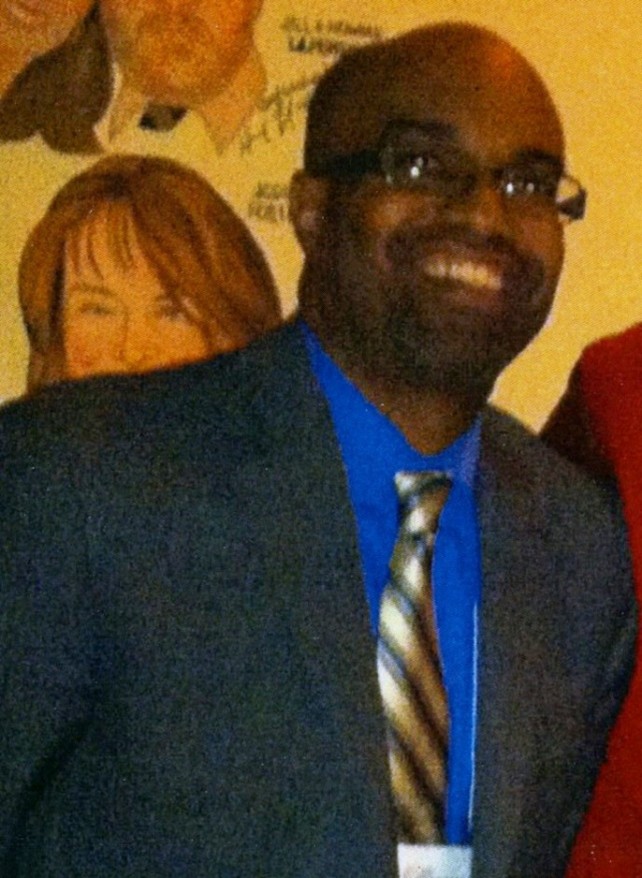

Ron Buckmire

Ron Buckmire at the 2013 Joint Mathematics Meeting. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ron_Buckmire_at_2013_Joint_Mathematics_meeting.jpg

Ron Buckmire is an applied mathematician whose work spans numerical analysis, mathematical modelling, and mathematics education. Beyond his research, he has played a major role in LGBTQ+ advocacy within STEM. Buckmire was a founding member of Spectra, the association for LGBTQ+ mathematicians, and has long championed greater visibility and representation for historically excluded groups. His activism and academic leadership make him a central figure in contemporary LGBTQ+ mathematical communities.

More information about the LGBTQ+ association Spectra can be found here: What we do – Spectra

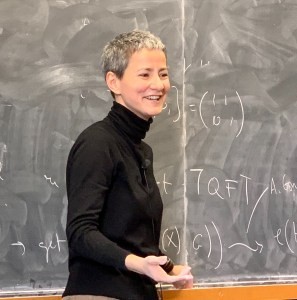

Marina Logares

Marina Logares. Source: https://lgbtqstem.com/2020/07/10/an-interview-with-marina-logares/

Marina Logares is an algebraic geometer whose work contributes to our understanding of complex algebraic structures. She is listed among confirmed LGBTQ+ mathematicians and is recognised for her visibility as a lesbian mathematician. Her presence in the field highlights the importance of representation and the work still to be done to ensure all mathematicians feel seen and supported in their academic environments.

You can read an interview with Marina, here: An interview with Marina Logares – LGBTQ+ STEM

We have picked out four examples of LGBT+ mathematicians for this blog, but there are many more inspiring mathematicians and statisticians, including those posted on the 500 Queer Scientists campaign, here. This visibility campaign which publishes self-submitted bios and stories intended to boost the recognition and awareness of queer scientists, including our own Senior Lecturer in Analysis: Tacey O’Neil. If you are LGBTQIA+ and work in STEM, STEM advocacy, STEM education (or any other supporting field), you can add your voice and story to 500 Queer Scientists.

OU academic Tacey O’Neil

Why Mathematics Belongs at the Heart of LGBT+ History Month

Rainbow Pi symbol.

Source: https://pixabay.com/vectors/pi-math-geometry-science-numbers-5786042/

Mathematics is often seen as abstract or detached from society, but in reality, it offers powerful tools for understanding and improving our world. Mathematical thinking helps us:

- Analyse inequalities through statistical evidence and modelling;

- Challenge assumptions by examining patterns and structures critically;

- Support inclusive policies through data driven decision making;

- Innovate responsibly, ensuring technologies reflect fairness and equity.

This year’s theme Science and Innovation, reminds us that progress depends not only on technological advances but also on the people behind them. When LGBTQ+ mathematicians can contribute openly and authentically, the entire discipline grows richer.

LGBT+ History Month is a moment to learn from the past, recognise present contributions, and work towards a future where all students and researchers feel welcomed and valued in mathematics.

Sources of further information and support

The LGBTQ Hub hosts a collection of free resources exploring sexuality and LGBTQ+ history across the core faculty areas within The Open University: LGBTQ Hub | OpenLearn – Open University

For OU students, you can find Open University Library resources here: LGBTQ+ | Library Services | Open University

You can find out about the Queer, Equality and Diversity (QED) Network for Maths, here: QEDNetwork

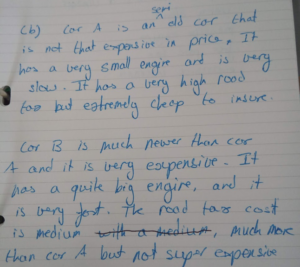

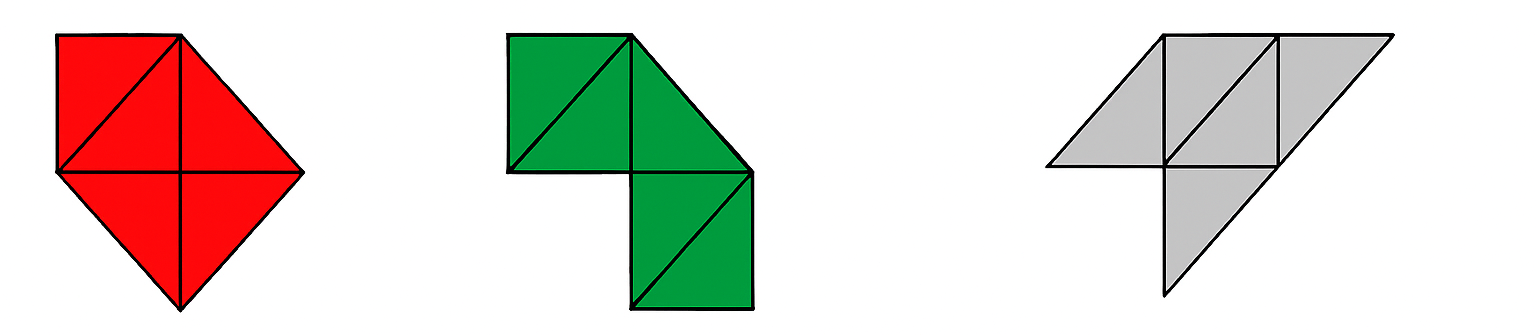

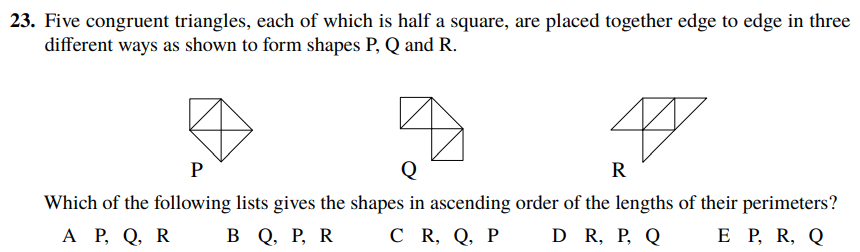

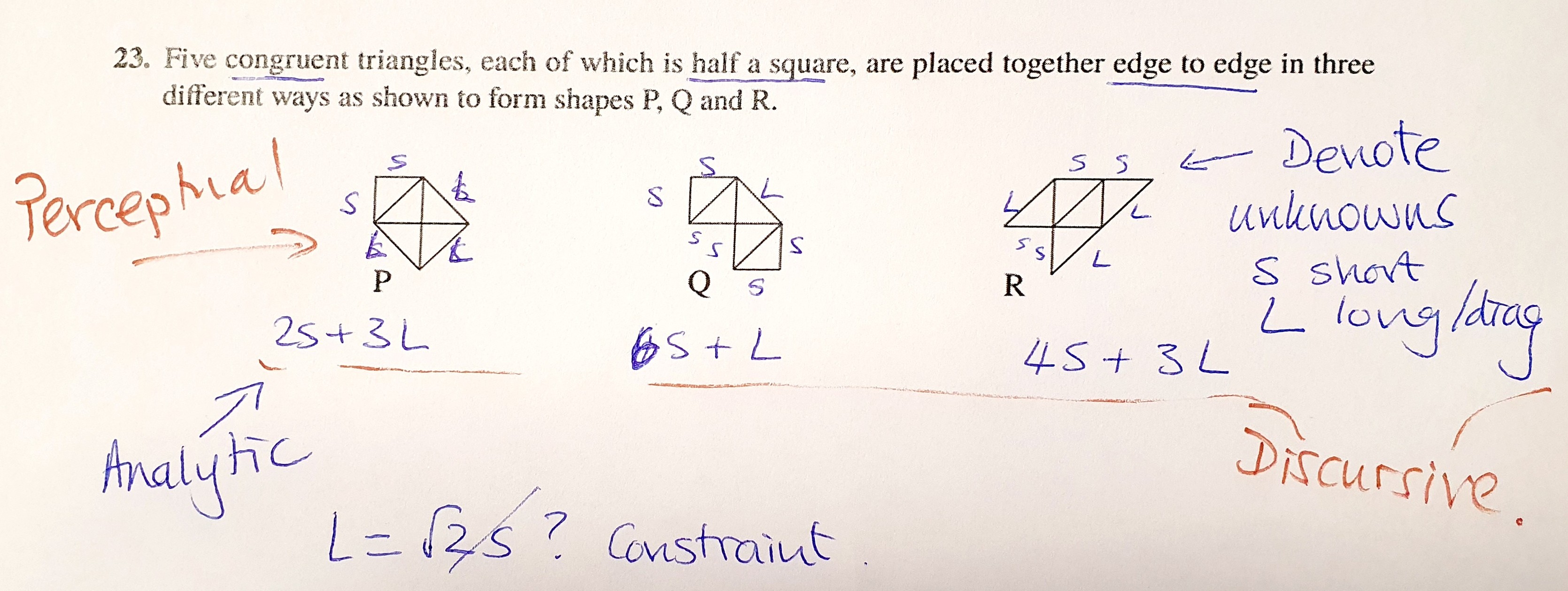

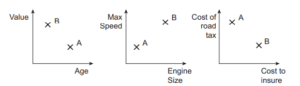

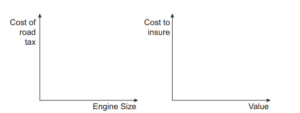

I mentioned that she need not give exact values, only its relation to the other car, for example, ‘Car A is older than B.’ She used this language when reasoning her responses to the statements. For statement (a)(i), she answered ‘False, car B is more expensive because it is younger.’ I re-phrased the question to, ‘Ignoring age, which car is more expensive?’ (I will elaborate why later, but I wanted her to practise using the y-axis.) She finished the remaining statements without much difficulty and gave good descriptions of the cars that I recorded.

I mentioned that she need not give exact values, only its relation to the other car, for example, ‘Car A is older than B.’ She used this language when reasoning her responses to the statements. For statement (a)(i), she answered ‘False, car B is more expensive because it is younger.’ I re-phrased the question to, ‘Ignoring age, which car is more expensive?’ (I will elaborate why later, but I wanted her to practise using the y-axis.) She finished the remaining statements without much difficulty and gave good descriptions of the cars that I recorded.