This post is the English translation of a Welsh-medium article by Dr Gwenllian Lansdown Davies and Angharad Morgan written for a special edition of the Primary First journal, edited by the Open University’s Early Childhood team ( Journal – NAPE )

Mudiad Meithrin (originally Mudiad Ysgolion Meithrin) was established in 1971 to nurture and support a landscape of Welsh-medium play and learning experiences for children from birth to school age throughout Wales. Our vision is that every child in Wales should have the opportunity to play, learn and grow through the Welsh language. We are passionate about giving the Welsh language to the children of Wales, and believe that children benefit from being bilingual and multilingual. As an organisation, our aim is to develop, support, provide and facilitate childcare and Welsh-medium education in Cylchoedd Meithrin (playgroups) and registered day nurseries. Why then did we step into the field of publishing children’s literature?

Why children’s literature?

Like many other individuals and organizations across the world, the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis back in 2020 was the trigger for us to look objectively at our work, and we are now at the start of the journey to be an anti-racist movement.

Simply put, there are three main strategic drives to our work in this regard. Firstly, the curriculum for non-maintained funded nursery settings in Wales (namely Cylchoedd Meithrin and day nurseries) states the need to “ensure that every child has a strong sense of belonging, that they feel valued and represented in our setting”. Secondly, the Welsh Government’s commitment to developing Wales as an anti-racist nation by 2030 is an important target. Thirdly, it is the morallycorrect thing to do considering that the Welsh language belongs to everyone.

The concept of ‘cynefin’ – which is translated in English as ‘the place where we feel we belong’ – is a fundamental element of our curriculum. A wide range of research indicates the importance of ‘seeing myself’ in books and across various media for children and adults as a way of fostering a sense of belonging to a community.

In order to achieve these visions, our education and childcare systems need to expand the understanding and knowledge of children, young people and staff of the various cultures that are part of our past and present here in Wales. We must ensure that the ‘cynefin’ we present as part of our provision is inclusive.

The Welsh language has a rich history of telling stories, in print and orally. Nevertheless, one of the many challenges for our traditional institutions is to ensure that our Black, Asian and Ethnic Minority or Global Majority communities are seen as part of Welsh and Welsh-speaking life and culture.

Mudiad Meithrin has a history of publishing books for children since its establishment in the early 70s and the series of reports ‘Respecting Realities’ published by the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education since 2017 strengthens the argument to intervene in the market to ensure the presence of minority cultures in mainstream Welsh medium literature for children.

Our intention was therefore to support and stimulate work by Black, Asian and ethnic minority authors (or global majority) to produce work for children in Welsh. It was important for us to ensure that Black, Asian and ethnic minority individuals were part of the planning work and we had the support of several individuals including members of our Board of Directors.

From ‘Authors’/‘AwDUron’ …

Following the initial phase of planning, it was necessary to identify and seek various sources of funding to finance such a plan. We were fortunate to receive grants from the Welsh Government, a grant from a philanthropic fund, and crowdfunding to develop our vision. The funding is essential to ensure that the mentors and prospective authors receive payment for their commitment to the scheme.

The initial scheme ‘AwDUron’ was launched by specialist translation company ‘Lily Translates’ and Mudiad in 2022, with a call for authors from a global majority background to work together with us to translate books they had already published in English into Welsh.

The aim of the ‘AwDUron’ scheme was to give a voice and a platform to Black, Asian and ethnic minority communities to write, create and publish stories for children in Welsh so that children see themselves and the diversity of our country in books.

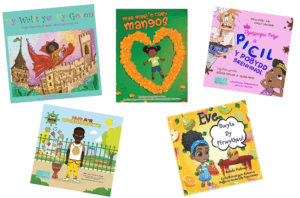

The ‘AwDUron’ scheme has led to the publication of 5 new books in Welsh:

- Jojo a’r Adinkrarwyr (Jojo and the Adinkrars) by Jodi Twum-Barima;

- Eve, Bwyta dy Ffrwythau (Eve, Eat Your Fruit) by Adele Palmer;

- Y Dywysoges Priye & Picil y Pobydd Brenhinol (Princess Priye & Pickle the Royal Baker) by Jessica Taylor and Olivia Priye;

- Mae Mari’n Caru Mangos (Mari loves mangoes) by Marva Carty;

- Dy Wallt yw Dy Goron (Your Hair is Your Crown) by Jessica Dunrod.

… to ‘Author’/’AwDUra’

What then is the difference between the ‘AwDUron’ scheme and the ‘AwDUra’ scheme? The two names are actually a play on words: ‘awdur’ (the Welsh word for author) and ‘awdura’ (the verb for ‘to author’)… and both contain the Welsh word ‘DU’ (Black). The emphasis of the ‘AwDUron’ scheme was to translate work that already existed in another language. The aim of ‘AwDUra’ on the other hand is to support authors to develop original work in the Welsh language. As explained above, the ‘AwDUra’ scheme was introduced in partnership with ‘Lily Translates’ (and the author Jessica Dunrod), the first translation company in the UK that specializes in translating children’s literature.

In order to do this, we have to overcome the challenges that come with encouraging new writers to write in a minority language – which may actually be their 2nd or 3rd language – and which they may not engage with outside of a formal, academic environment.

From the applications to ‘AwDUra’, ten candidates were selected to be part of a mentoring and support process by Manon Steffan Ros (prolific author and Carnegie medal winner) and Jessica Dunrod (author and founder of ‘Lily Translates’). The process included workshops, one to one meetings and opportunities to listen to other published authors such as Marva Carty and Dr Ishani Kar-Purkayastha.

All authors received support and feedback from internationally renowned authors and industry mentors, encouraging them to continue to create quality children’s literature even after the project ended.

Ultimately, 4 works were chosen to be published based on their content, their storytelling skills and their relevance to ‘Cynefin’ and the Curriculum for Wales – books by Chantelle Moore, Theresa Mgadzah Jones and Mili Williams together with a cartoon by Sarah Younan published in the magazine ‘Wcw’ (in partnership with Cylchgronau Golwg Cyf.). Here are the details of the books:

- Y Brenin, Y Bachgen a’r Afon (The King, The Boy and the River) by Mili Williams

- Mamgu, Mali a Mbuya (Grannie, Mali and Mbuya) by Theresa Mgadzah Jones

- Granchie a’r Dderwen Fawr (Granchie and the Great Oak) by Chantelle Moore

A few other participants – Natalie Jones and Nia Morais – continued to develop their creative work with other publishers and also produced important resources for us (a resource on John Ystumllyn and a poem). The AwDUra scheme has shown that, by working together with authors, publishers, and critical friends, positive and constructive steps can be taken to improve the representation of Global Majority communities in original Welsh literature.

Books on the Web

Following a successful application to the Windrush Cymru fund in 2024, we set about developing a digital, visual version of Chantelle Moore’s book, Granchie a’r Dderwen Fawr. The video has been published on our YouTube Channel for children – Dewin a Doti Channel. Here you can also see the presenter Seren Jones reading the book ‘Mam-gu, Mali a Mbuya’. These are invaluable resources that are freely available to everyone.

Where Next?

Mudiad Meithrin is still learning. But the scheme has also borne fruit more widely… as the authors go to present their books in schools, libraries and bookshops across Wales. In addition, we see anti-racism conferences referring to the importance of the anti-racist Welsh bookshelf, blogs about the history and development of ‘AwDUra’ being published on our website, collaboration with the National Library in Aberystwyth, and seeing increasing pressure on other bodies to reflect on their contribution to this crucial field. Mudiad publishes countless resources that are anti-racist in nature: from resources about nursery rhymes in various languages, to ‘Cymru Ni’ (resources about Black Wales) to a ‘Cylch for all’ inclusiveness pack, a ‘Come and Celebrate’ religion pack and strategic and practical collaborations with DARPL providing anti-racist professional learning opportunities, creating useful guidelines for the childcare sector and producing resources on understanding anti-racism in its historical and political context.

We have now bought the book rights to ‘Dy Wallt yw Dy Goron’ and have republished it under the name of Mudiad Meithrin.

We continue to look for funding that will enable us to develop the scheme further. Our hope is to be able to fund the ‘AwDUra 2’ scheme to respond to the need to develop creative and educational resources to support learning and teaching which is in line with the Curriculum for Wales and which builds on the foundations laid by the original ‘AwDUra’ programme. This will contribute towards ensuring that all Welsh children see themselves reflected in their resources and contribute constructively to creating an anti-racist atmosphere in the Cylch Meithrin, the nursery and the classroom.

Above all, we are passionate that we want to continue to encourage authors from a Global Majority background to write for children and to write in Welsh; to create a sense of belonging; to celebrate an inclusive environment; and to celebrate the diversity of Wales in the visual and literary representations of our children.

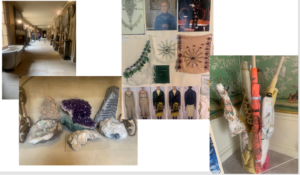

that it was just another gloomy albeit grand room, with a shiny statue. I loved the shock as I approached the statue and realised what it was. I was unaware of this story but was intrigued by it. The notes said to look for the secret door to the right of the statue, but I was unable to find this and found it another irritating example of keeping secrets and withholding information. I absolutely loved the sculpture because it seemed so transgressive and shocking. I also appreciated the pain of all humanity across the saint’s face. I don’t know a lot about Damian Hirst, apart from recognising his more famous pieces of work, but I loved the creativity, the humour almost in the saint having his skin draped over his arm – humour in the grotesque. I don’t appreciate the constraints of religion – thinking about my own childhood, so to have this disruption in the middle of the pomposity of an ornate chapel appealed to my sense of resistance and pushing back. I also appreciated the lovely symmetry of ideas of the skin as clothing with the upstairs exhibition and the draping of fabric; in fact, symmetry was an idea I seemed to focus on in many of the spaces.

that it was just another gloomy albeit grand room, with a shiny statue. I loved the shock as I approached the statue and realised what it was. I was unaware of this story but was intrigued by it. The notes said to look for the secret door to the right of the statue, but I was unable to find this and found it another irritating example of keeping secrets and withholding information. I absolutely loved the sculpture because it seemed so transgressive and shocking. I also appreciated the pain of all humanity across the saint’s face. I don’t know a lot about Damian Hirst, apart from recognising his more famous pieces of work, but I loved the creativity, the humour almost in the saint having his skin draped over his arm – humour in the grotesque. I don’t appreciate the constraints of religion – thinking about my own childhood, so to have this disruption in the middle of the pomposity of an ornate chapel appealed to my sense of resistance and pushing back. I also appreciated the lovely symmetry of ideas of the skin as clothing with the upstairs exhibition and the draping of fabric; in fact, symmetry was an idea I seemed to focus on in many of the spaces.

When I reflect back on my visit my immediate thoughts are about invisible boundaries. As I went around the house I took photos from a child’s-eye perspective, trying to see the contents and experience the spaces from their viewpoint. This meant that I had pictures of key holes, door stops, table legs and other random items. Towards the end of the visit a security guard approached me to ask if I had been taking pictures of door handles, what my photographs might be used for and generally finding out what I was doing. During the conversation I realised that actually, there could be a malevolent reason for taking these pictures, and I also realised that the staff in each room and corridor had been watching and raising concerns with the security team. When it became apparent that I wasn’t up to no good we had a great chat about the exhibition, the work that the Chatsworth education team do and I went on my way. But when I looked back at my photographs the incident coloured my recollections, I found myself thinking ‘should I have been looking at that’? Was I supposed to be in that space? Was I doing things ‘right’?

When I reflect back on my visit my immediate thoughts are about invisible boundaries. As I went around the house I took photos from a child’s-eye perspective, trying to see the contents and experience the spaces from their viewpoint. This meant that I had pictures of key holes, door stops, table legs and other random items. Towards the end of the visit a security guard approached me to ask if I had been taking pictures of door handles, what my photographs might be used for and generally finding out what I was doing. During the conversation I realised that actually, there could be a malevolent reason for taking these pictures, and I also realised that the staff in each room and corridor had been watching and raising concerns with the security team. When it became apparent that I wasn’t up to no good we had a great chat about the exhibition, the work that the Chatsworth education team do and I went on my way. But when I looked back at my photographs the incident coloured my recollections, I found myself thinking ‘should I have been looking at that’? Was I supposed to be in that space? Was I doing things ‘right’?

On June 26th 2024 Dr Natalie Canning presented her Empowerment Framework at a breakfast event held in the British Library in London. The organisations who attended the event neatly illustrated how ‘early childhood’ is an umbrella term, with representatives that work with babies, pregnant mothers, early childhood and care settings, and childminders as well as early childhood researchers, practitioners, policy influencers and members of the EC@OU team. The work being done by these groups reaches across the UK nations and beyond.

On June 26th 2024 Dr Natalie Canning presented her Empowerment Framework at a breakfast event held in the British Library in London. The organisations who attended the event neatly illustrated how ‘early childhood’ is an umbrella term, with representatives that work with babies, pregnant mothers, early childhood and care settings, and childminders as well as early childhood researchers, practitioners, policy influencers and members of the EC@OU team. The work being done by these groups reaches across the UK nations and beyond.