Historical themes in the Diocese of London: Researching faith and worship

Researching faith and worship

In the modern period we have significant advantages over medievalists in the plethora of printed sources which record what was said or done in church, and even some sources to indicate what congregations made of what was on offer! The fact that then as now London offered a remarkably rich melting pot means that there are also some specific sources available for religious life of the capital that we do not have for other parts of Britain. Of course faith often found its expression in works, and it is important not to neglect the evidence to be garnered from the records of missionary activity and evangelism, or social work. These are discussed under outreach and social issues in this resource guide, as are the sources for the changing architecture and fittings of churches, which also give important clues. And finally for an individual, almost any biographical source you can find might give some clues: however, it is the case that for all the prominence of religion to the Victorians, they could be coy on the details of ecclesiastical allegiances as opposed to merely expressing conventional piety.

There follow some suggestions on where to look!

Accounts of church services/modes of worship

There is no systematic way of recovering information on this, and it is rather a case of trying various different tacks to see what if anything comes up trumps. It is important not to neglect the value of mundane sources: parish archives might just contain a service register, for example, which might give valuable information on the patterns of worship in a particular church, or parish magazines or newsletters.

Another potential source that may give more detail about the content of services and the way the church was ornamented and used can come from answers to visitation queries issued by the bishop or archdeacon. They were not the only ones to ask such questions, however. As church disputes over the conduct of services and ritualism in particular escalated in the later nineteenth century both newspapers and private individuals took a considerable interest in what went on in churches. If there was a local controversy you are likely to find (sometimes not very accurate!) accounts in newspapers and possibly correspondence relating to the dispute being written to the bishop. There were also a number of surveys and guides to services published at different dates.

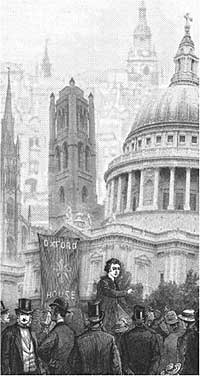

This extract from Bishop Tait’s diary, held at Lambeth Palace Library, gives a list of preaching his engagements in the diocese. (Image courtesy of the Trustees of Lambeth Palace Library).

One resource which is often neglected is the sermon. Judging by the groaning shelves of copyright libraries, the Victorians had an almost insatiable appetite for sermons, both in terms of turning up to hear them, and for reading them for entertainment or edification once they got home. Clergy often struggled to keep up with demand (indeed the lazy could purchase sermons printed to appear as if handwritten when taken into the pulpit!). Publishers did a roaring trade both in collections of sermons and in pamphlet publication of single ones. Although many make for leaden reading, even these can illuminate what the atmosphere was like in the church where they were delivered and may even include comments on reception. At their best, however, sermons were miniature masterpieces of prose and thought, profound and moving reflections on both theological issues or pressing issues of the day. You may find deep reflections on the Easter story, or a ferocious response to political disorder, hunger, cholera, or economic injustice from a variety of political perspectives. As the twentieth century proceeded, the public's appetite for sermonizing diminished (though some clergy merely transferred their contribution to literature to the comment columns of the burgeoning metropolitan press), but even then clergy could make a bigger impact from a pulpit than is conceivable today. See here for information on where you can read sermons preached in London churches.

The Victorian presses like those of previous centuries churned out religious literature in extraordinary quantities, and the volume was still considerable in the early twentieth century. It would be impossible to give more than a very cursory account of what is available in terms of researching the tenour of religion in the past through such writing. However, one should caution against assuming that the great classics of Victorian devotional literature necessarily give an insight into the mind of the man or woman in the pew. Any major library will hold substantial collections, and of course that at Lambeth Palace Library is very strong. Some classics of Victorian devotional writing can be obtained via Google books; if you don't know what to look for, a good place to start is the collection of freely available texts at the Project Canterbury website.

What can I read on other religious traditions and unbelief?

There are some useful essays on all the themes that follow in

Gerald Parsons (ed.), Religion in Victorian Britain, 4 vols. (Manchester University Press, 1988), esp. vols. 1, 2, 4.

For other Christian denominations, see for Protestant Dissent:

Michael Watts, The Dissenters vol. 2: The Expansion of Evangelical Nonconformity (Oxford University Press, 1995)

For Roman Catholicism

E. R. Norman, The English Catholic Church in the Nineteenth Century (Oxford University Press, 1985)

Mary Heimann, Catholic Devotion in Victorian England (Oxford University Press, 1995)

For irreligion:

Susan Budd, Varieties of Unbelief: Atheists and Agnostics in English Society 1850-1960 (Heinemann, 1977)

Timothy Larsen, Crisis of Doubt: Honest Faith in nineteenth-century England (Oxford University Press, 2006)

David Nash, Blasphemy in Modern Britain : A History 1789 to the Present (Ashgate, 1999)

A good place to look for further reading is on the website of The Victorian Web, with its extensive resources and bibliography.